|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_United_Nations.svg While the ideals of the United Nations (UN) are commendable, it seems obvious that the UN as an organization is deeply troubled and bordering on irrelevancy. Its system of governance is paralyzed, its decisions partisan, its leaders suspect, its resolutions flouted, and its ideals lost in the passions of political brinkmanship. Some call for its demise. Most ignore it.

Yet what many people do not know is how the churches at one time were enthused with the UN and saw it as a way forward in a troubled world. Consider the case of Canadian churches.

0 Comments

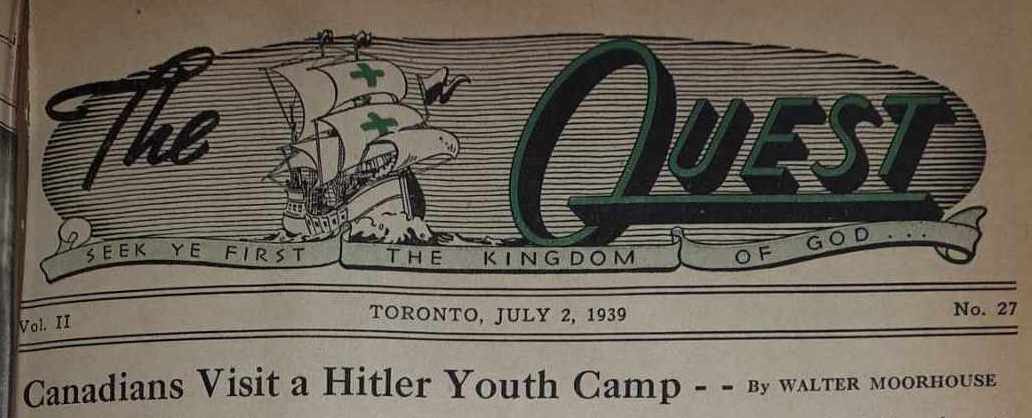

A while ago I was looking through Canadian Baptist periodicals in the archives at McMaster Divinity College and I made a serendipitous discovery of an article that described a visit of Canadian youth to a summer Hitler Youth Camp. This discovery is an excellent example of finding something from the past that makes little sense in the present.

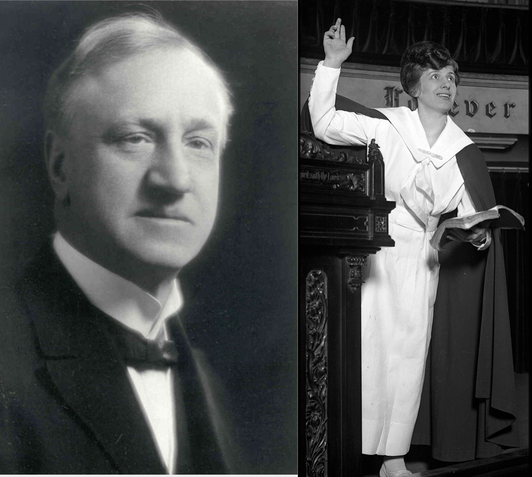

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Aimee_Semple_McPherson-AngelusTemple_Sermon_1923_01.jpg One of the enjoyable aspects of archival research is the possibility of serendipitous discoveries – such as the account of T.T. Shields covertly attending an Aimee Semple McPherson service.

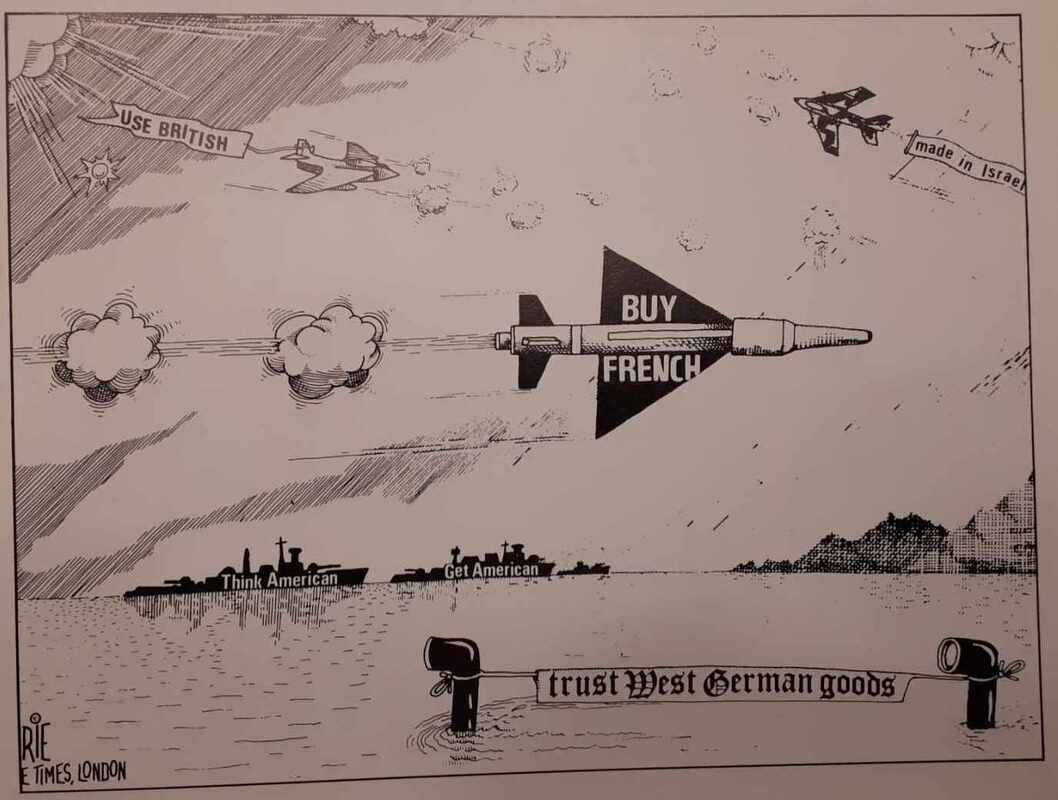

As the above and below advertisements from the War in the Falklands (1982) indicate, wartime is considered by some to be an ideal time to test the usefulness of old weapon systems and try out new ones. It is also a chance for companies to gain market share in the lucrative billion-dollar global arms trade.

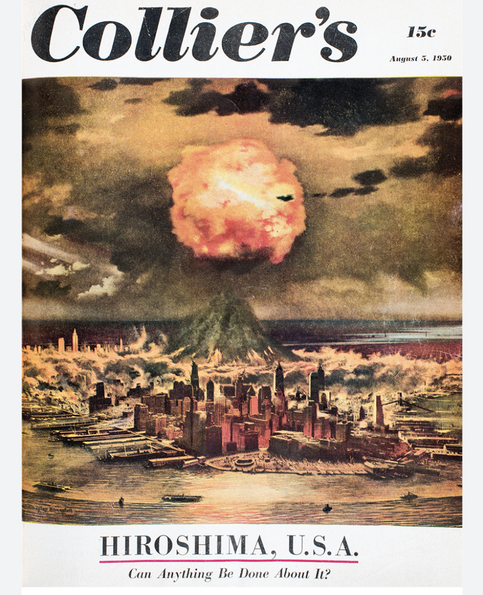

And that is what is now taking place in the war between Russia and Ukraine. For details on this issue of Collier's, see https://lithub.com/new-york-city-the-perfect-setting-for-a-fictional-cold-war-strike/ There are many things to consider when building highways in and out of our cities today. But one thing probably none of us have considered since the end of the Cold War is the need for citizens to get out of urban centres rapidly before they are incinerated in a nuclear attack.

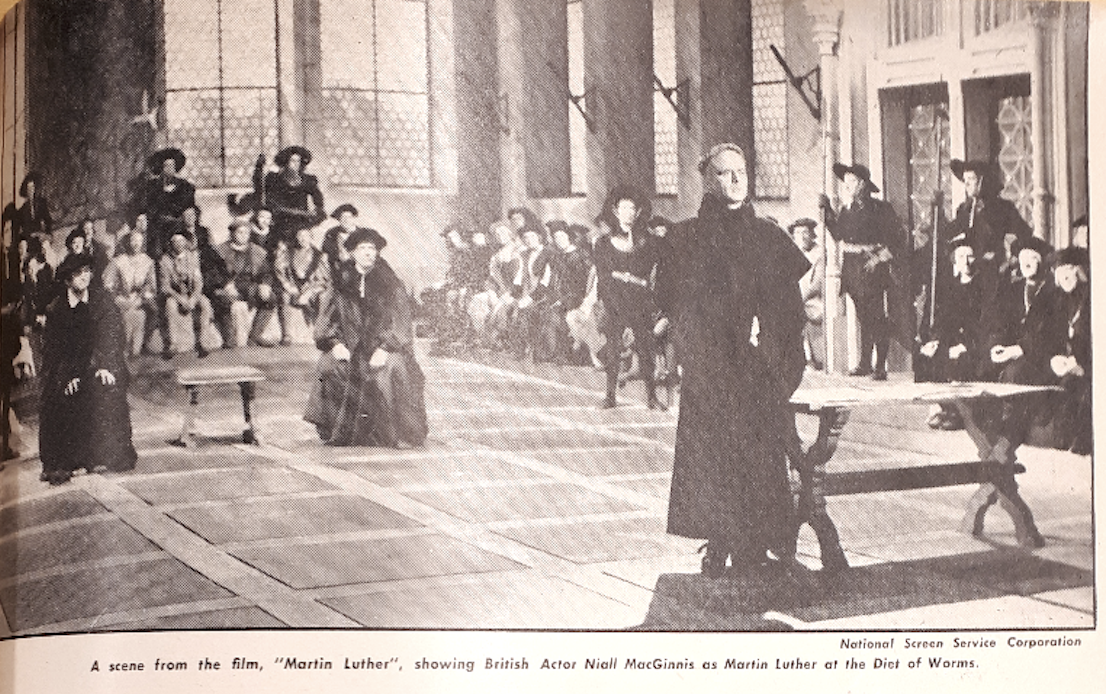

But that was in the mind of US President Eisenhower in the nerve-wracking Cold War days of the 1950s. I am teaching a class on the Reformation this semester, and to get students into the drama of the period I like to show a brief movie clip of Martin Luther making his iconic “Here I Stand” speech at the Diet of Worms (1521). There were a number of iconic moments in his life but that was probably one of the most poignant, dangerous, and well known.

But what few know is that a movie on Luther was banned in theatres in Quebec in the 1950s.[1] Most Canadians know about the impressive Canadian success in the Battle of Vimy Ridge that was fought in the First World War on the Western Front (April 1917). From that success onwards it was increasingly seen by Canadians as a glorious nation-building battle that proclaimed to the world that Canada was not a mere colony of the British Empire, but increasingly a peer worthy of national status.

But few Canadians know that there was a battle that predated Vimy, a battle fought not in Europe but in Africa. And in its day it was seen by Canadians to be the nation-building battle where Canada had demonstrated its military prowess and its maturity as a growing Dominion. The battle was the Battle of Paardeberg (18-27 February 1900). And the war was the South African War, 1899-1902 (often called the Boer War). Some words should rarely be used and instead be saved for only the most extreme circumstances. If overused, such words will lose their power. And if that happens, we are left in the dangerous situation of not having the vocabulary to deal with a crisis.

One such word is “genocide”. Canada is facing a housing crisis marked by unaffordable houses, lack of homes, ridiculously high rental costs, and a dismal failure to build enough units to alleviate the crisis. And inflation and high interest rates pile on even more pressures. As a result, countless people are homeless, living in undesirable conditions, or even on the streets. It is a complete mess with no end in sight.

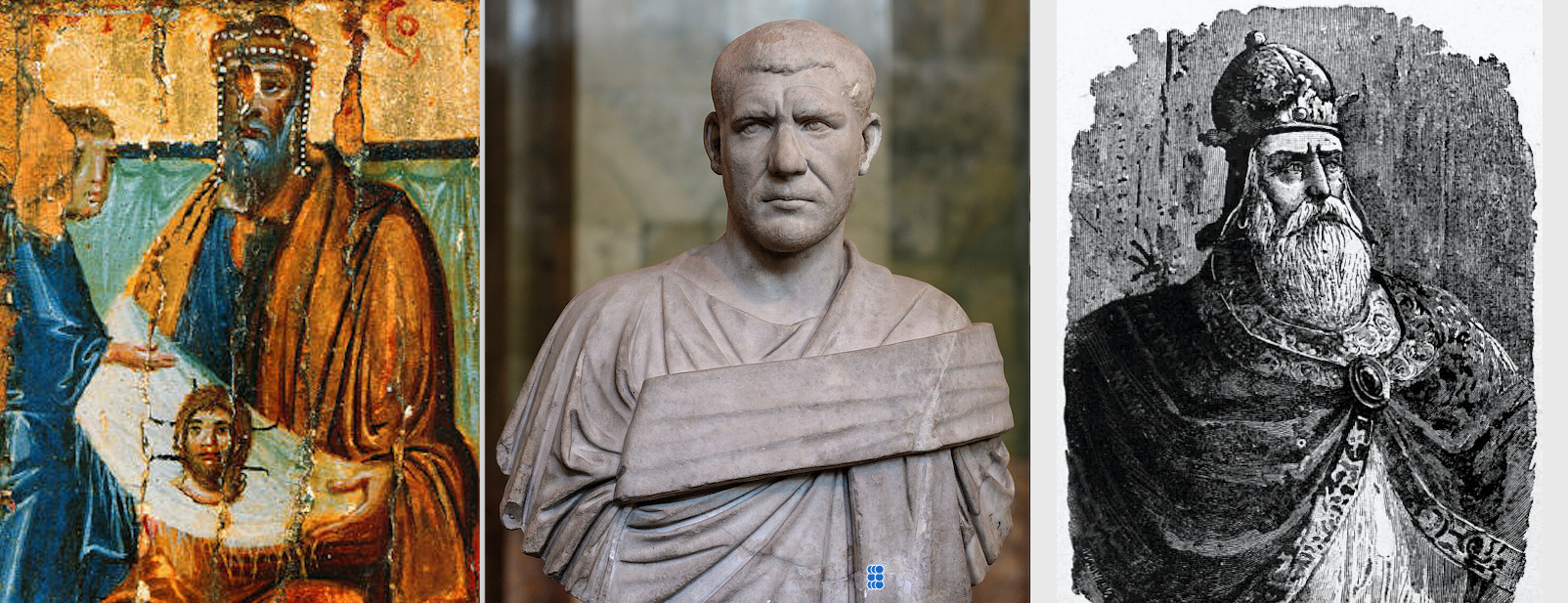

But as I recently discovered it is not the first time Canada has gone through a housing crisis. While recently reading some church periodicals from the later years of the Second World War and the immediate postwar period I discovered some commentary on what the churches considered to be a pressing and alarming housing crisis. What follows are some brief observations on the churches’ response. images from wikipedia One of the most well-loved Christmas carols is “We Three Kings,” a hymn about the Matthew 2:1 account of the visit of Magi from the East to see the young Jesus. The biblical record indicates that they brought three gifts, but it provides no number of how many wise men arrived to see Jesus. While those unidentified wise men seem to get all the attention, what is little known is that there were accounts from the world of antiquity between the adult ministry of Jesus and the conversion of Constantine the Great of three kings who identified as Christians. The evidence for these three men is sparse and perhaps in some cases a bit sketchy. Most people today have not heard of them. And they have nothing to do with Christmas. Nevetheless, I find them fascinating. Many more Christian Kings (and Queens) converted to the faith in subsequent centuries, but it is worth noting here the first three in chronological order. Enjoy.

Eusebius the church historian records the conversion of King Abgar V of Edessa during Jesus’ ministry. According to the account he eventually responded positively to the missionary efforts of Thaddeus of Edessa, one of the seventy disciples sent out by Jesus.[1] What is fascinating is the supposed letter written by Jesus to the King that was kept in the archives in Edessa. Here is the account of his conversion as recorded by Eusebius in his Church History. “The divinity of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ being reported abroad among all men on account of his wonder-working power, he attracted countless numbers from foreign countries lying far away from Judea, who had the hope of being cured of their diseases and of all kinds of sufferings. For instance the King Abgarus, who ruled with great glory the nations beyond the Euphrates, being afflicted with a terrible disease which it was beyond the power of human skill to cure, when he heard of the name of Jesus, and of his miracles, which were attested by all with one accord sent a message to him by a courier and begged him to heal his disease. But he did not at that time comply with his request; yet he deemed him worthy of a personal letter in which he said that he would send one of his disciples to cure his disease, and at the same time promised salvation to himself and all his house. Not long afterward his promise was fulfilled. For after his resurrection from the dead and his ascent into heaven, Thomas, one of the twelve apostles, under divine impulse sent Thaddeus, who was also numbered among the seventy disciples of Christ, to Edessa, as a preacher and evangelist of the teaching of Christ. And all that our Saviour had promised received through him its fulfillment. You have written evidence of these things taken from the archives of Edessa, which was at that time a royal city. For in the public registers there, which contain accounts of ancient times and the acts of Abgarus, these things have been found preserved down to the present time. But there is no better way than to hear the epistles themselves which we have taken from the archives and have literally translated from the Syriac language in the following manner.” [Copy of an epistle written by Abgarus the ruler to Jesus, and sent to him at Jerusalem by Ananias the swift courier] “Abgarus, ruler of Edessa, to Jesus the excellent Saviour who has appeared in the country of Jerusalem, greeting. I have heard the reports of you and of your cures as performed by you without medicines or herbs. For it is said that you make the blind to see and the lame to walk, that you cleanse lepers and cast out impure spirits and demons, and that you heal those afflicted with lingering disease, and raise the dead. And having heard all these things concerning you, I have concluded that one of two things must be true: either you are God, and having come down from heaven you do these things, or else you, who does these things, are the Son of God. I have therefore written to you to ask you if you would take the trouble to come to me and heal the disease which I have. For I have heard that the Jews are murmuring against you and are plotting to injure you. But I have a very small yet noble city which is great enough for us both.” [The answer of Jesus to the ruler Abgarus by the courier Ananias] “Blessed are you who hast believed in me without having seen me. For it is written concerning me, that they who have seen me will not believe in me, and that they who have not seen me will believe and be saved. But in regard to what you have written me, that I should come to you, it is necessary for me to fulfill all things here for which I have been sent, and after I have fulfilled them thus to be taken up again to him that sent me. But after I have been taken up I will send to you one of my disciples, that he may heal your disease and give life to you and yours.” Eusebius, Church History, 1.13.[2] See the Armenian bank note below that commemorates King Abgar.

The details surrounding Philip’s Christian identity are uncertain, but there are some compelling reasons to believe that he was the first Roman emperor to convert to the faith. Philip was born in Arab lands to the east of the Sea of Galilee and the Empire. He rose through the ranks and eventually briefly became an emperor (244-249). However, he was killed by a competing emperor named Decius. His short reign during turmoil meant that – even if he was a Christian – his impact on the fortunes of the church was negligible. Evidence for his conversion can also be found in early church writings such as Eusebius’ Church History. “Gordianus had been Roman emperor for six years when Philip, with his son Philip, succeeded him. It is reported that he, being a Christian, desired, on the day of the last paschal vigil, to share with the multitude in the prayers of the Church, but that he was not permitted to enter, by him who then presided, until he had made confession and had numbered himself among those who were reckoned as transgressors and who occupied the place of penance. For if he had not done this, he would never have been received by him, on account of the many crimes which he had committed. It is said that he obeyed readily, manifesting in his conduct a genuine and pious fear of God.” Eusebius, Church History, 6.34[3]

While the beginnings of what we call Christendom are usually traced to events in the Roman Empire, the earliest instance of an established church can be found in Armenia under the reign of King Tiridates III (also known as King Tiridates the Great, and the Armenian Church also calls him St. Tiridates). We know of him primarily through the history of Armenia written by Agathangelos. Some of the events surrounding the conversion of the King of Armenia and the role of Gregory the Illuminator (the Christian missionary involved in the king’s conversion) are a bit sketchy due to deciphering fact from fiction in hagiography. What is generally accepted is the fact that King Tiridates was converted around 301. After his conversion, and with the encouragement of Gregory, the king built a series of churches throughout Armenia and introduced Christian liturgy to Armenia. Gregory also encouraged the mass conversion of Armenia, and, as a result, the king ordered all pagan shrines to be torn down. Gregory baptized close to 200,000 people into the new faith, so much so that by the fifth century the faith had become fairly well established, and Armenia was what we today call a “Christian nation.” What is interesting is that the Armenian Church has a hymn noting three great kings in their history, a hymn called "To the Kings." King Tiridates III is one of those kings. Here is a brief account of his conversion (the actual account is quite long): “When they had all been convinced to worship the only true God, Gregory and Tiridates began traveling to other parts of the country to instruct the people and to destroy the altars of the false gods. In many of the provincial towns, demons in the form of armed soldiers fought against the evangelist's efforts. They were put to flight each time, and then Gregory would tell the people not to be afraid, but to drive out their own personal demons of false worship, and follow Christ. He performed miracles to show the people how loving and powerful God is. And the king gave testimony about his sinful acts, and the miracles and mercy of healing which God had shown him. So they traveled through the provinces and everywhere they spread the light of the Gospel and destroyed the dark pagan superstitions which had held the people captive. After they returned to Vagharshapat, Tiridates called together all his courtiers and the leaders from every corner of the land. The king wanted to make Gregory their pastor, so that everyone could be baptized and begin in earnest to live the new life in Christ. Gregory protested his unworthiness, but Tiridates had a wonderful vision from God urging him to carry out his plan, and the angelic vision also appeared to Gregory, telling him not to thwart it. So Gregory said: ‘Let God's will be done.’” Agathangelos, History of St. Gregory and the Conversion of Armenia [4] [1] Eusebius, Church History 1.13 [2] https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250101.htm [3] https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/250106.htm [4] https://www.livius.org/sources/content/agathangelos/agathangelos-history-3/ |

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed