|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

On my recent trip to some conferences in San Antonio, Texas, I walked over to a Sunday morning mass at the San Fernando Cathedral (also known as Cathedral of Our Lady of Candelaria and Guadalupe). I have been to several masses in various churches in Canada, and I thought this service would be just like the others over the years. But there were a few surprises for me that morning.

1 Comment

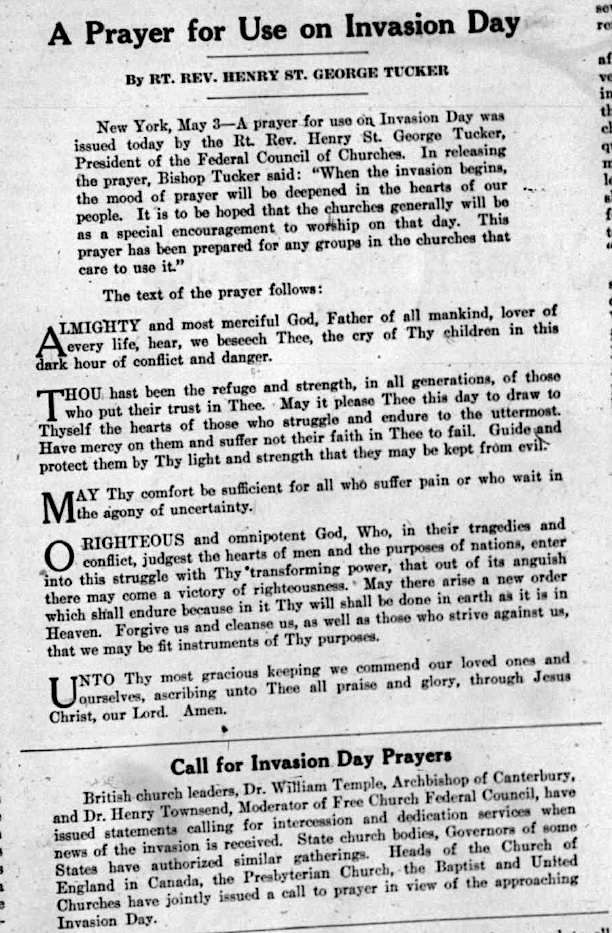

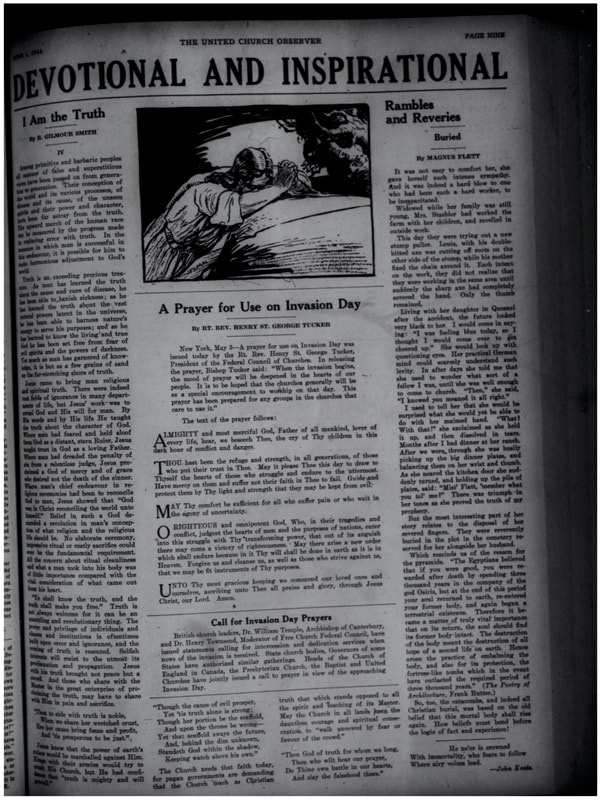

The prayer noted above was published by Henry St. George Tucker in the United Church Observer (1 June 1944). As Adam Rudy and others have noted, the Canadian churches were active supporters of the war effort against Germany and Japan. And with the long-anticipated invasion looming in Western Europe the churches took it upon themselves to pray for success on the beaches and beyond. Note, however, the lack of wild jingoism and the presence of an attitude of humility - included within the prayer is a recognition of the Allies' sins, as well as the hope for a better future among all nations. On this Remembrance Day may we remember and honour those who have come before us, and paid a high price for our liberty. Below is the full page. (Sorry the image is crooked - I was unable to adjust the image.) For further reading on the church and the war, see Adam Rudy, "The Cause of Righteousness and Freedom: Canadian Protestant Churches and the Second World War," PhD dissertation, McMaster Divinity College, 2022. Sadly, there is no complete work on the Catholic churches in Canada for the period of the Second World War.

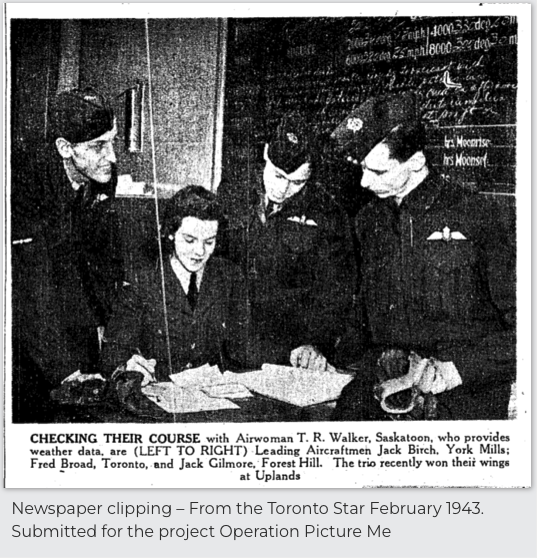

Before my dad moved to England in 1998, he took me aside and gave me a precious keepsake he had held since the Second World War. I had never seen it before. It was a scarf worn by his cousin Frederick Heath Broad (1923-1944) in the local Cub Scouts group in Toronto. The reason for the transfer of ownership to me was that my dad did not want it to get lost as he relocated across the Atlantic to England.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:IAF-F-35I-2016-12-13_(cropped).jpg In the ancient myth of Scylla and Charybdis, ships attempted to navigate between a treacherous sea monster on the one side and dangerous rocks (or a whirlpool) on the other. One small mistake to the right or left meant disaster. And that story has become a modern-day parable about avoiding two looming and equally dangerous extremes.

The crisis facing the Israeli government over the recent terrorist attacks by Hamas recalls (at least to my mind) that ancient myth. There are two dangers facing Israel, both with serious consequences. The first is to do not enough, the second is to do too much. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:St._Gregory_of_Nyssa.jpg It is easy to assume that “one size fits all” when instructing people about the essentials of the faith. Yet the early church leaders and the church fathers knew better. Stated simply, while there is only one apostolic faith, the way in which that faith is communicated must be adapted to different people in different times and in different places.

I was recently reminded of this when I bought a wonderful modern version of St. Gregory of Nyssa’s Catechetical Discourse. This work was a handbook of instruction for those who intended to teach the faith to others. Here is the remainder of my summer reading summary – a bit late, but, in this case, late is better than not at all!

“They didn’t teach me that at seminary!” is often a complaint of seminary graduates in the years following convocation. But is it a fair criticism? Can seminary really prepare people for literally every possible circumstance in life and ministry? And if they can’t, what was the point of all the books and papers?

The quick answer can be encapsulated in the aphorism “give people a fish, feed them for a day - teach people how to fish, feed them for life.” One advantage of having a cottage with no internet (and no data plan on my phone) is that I get a ton of reading done in the evenings. In fact, I think I will stay a luddite on this issue for the foreseeable future – it is simple too much of a boon to my page count to have no electronic distractions!

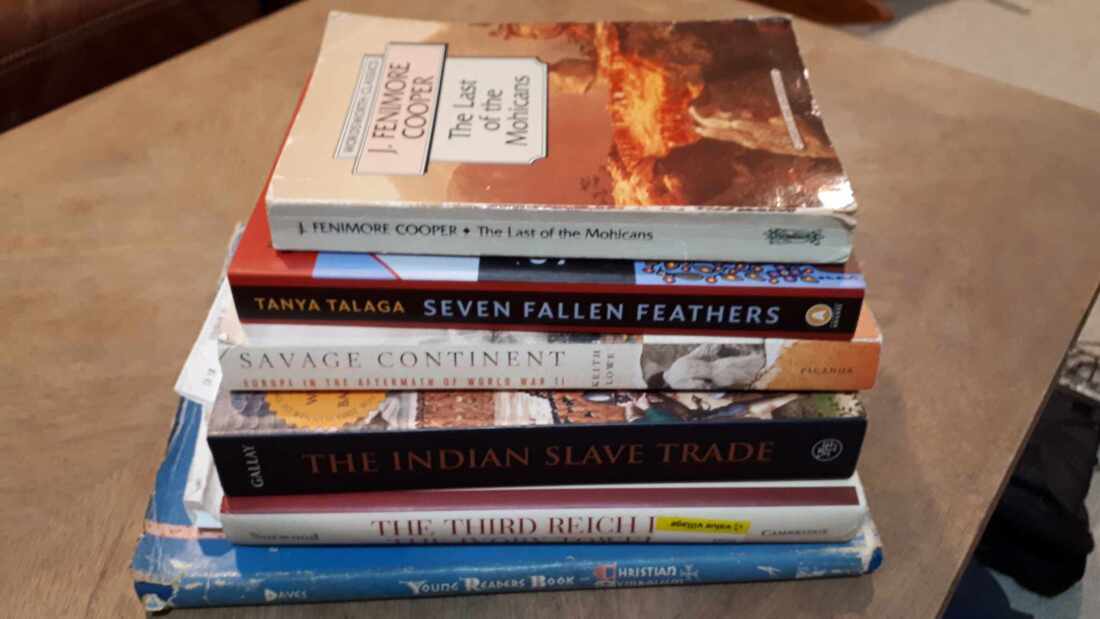

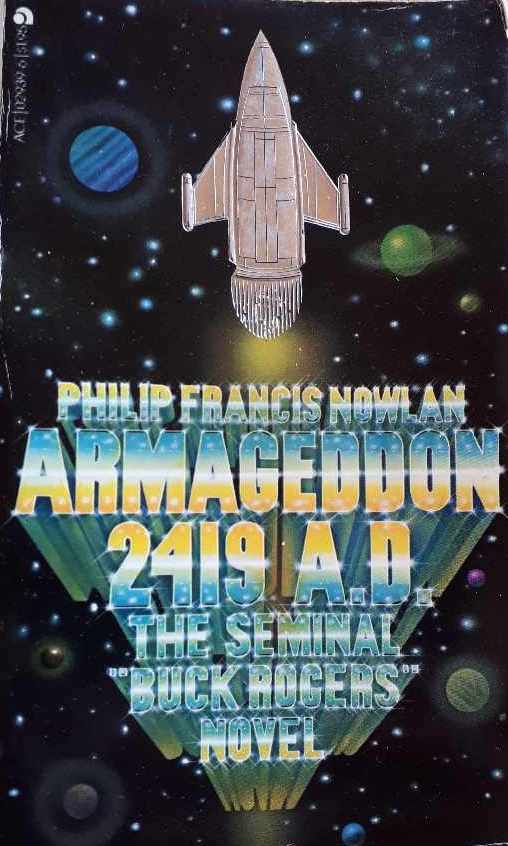

My reading this summer was very eclectic, and some books were only added to the list because they were fun and cheap discoveries at the used book section of our local cottage-country store. Here they are in no particular order along with a comment or two regarding their relative merit. I grew up hearing about the science fiction figure of Buck Rogers, but I never actually knew anything about him. All that changed a month or so ago when I found in a used bookstore an old copy of the first book in the Buck Rogers series. I quickly made the tough decision to spend the grand total of $1.50 to add it to my cottage summer reading list.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:President_Ronald_Reagan_and_Pope_John_Paul_II.jpg Protestants often think they are the cutting edge of Christianity. And evangelicals often tout their proclivity to adaptation and innovation. Yet can other Christian traditions claim innovation as well?

|

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed