|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

Niall Ferguson has rightly observed that “the worst time to live under imperial rule is when that rule is crumbling.” As an empire disintegrates, the loss of centralized power allows for old scores to be settled without fear of government crackdowns.

My previous post was on the rise, fall, or return of Christendoms. But what about Christian communities that face the violence that inevitably comes with no effective government at all? Will they continue to face violence or will they take up arms to defend themselves?

0 Comments

Christianity’s relationship with culture and the state has always been fluid, and developments over the past half a century have led to the rise, fall and return of Christendom in some old and new places. How those changes will impact the church’s view of war and violence is the focus of this blog.

[Note: “Christendom” is a term used to describe a church-state relationship marked by (1) the state identifying as Christian, (2) the church having a place of privilege over against other religions, (3) the church and state working in some sort of symbiotic partnership, and (4) the church being the primary shaper of culture.] My blogs on media in wartime are done. Now it is time to deal with the just war tradition and claims that it should be relegated to the dustbin of history.

British historian David Cannadine has rightly stated, “The older I get the more I’m convinced that it’s the purpose of politicians and journalists to say the world is very simple, whereas it’s the purpose of historians to say, ‘No! It’s very complicated.’”

If you think getting to the truth is complicated in peacetime, it is even worse in of times of war. The following are some final thoughts on the media and war. More specifically, there are three periods and two issues that need to be noted. For the past number of years people have heard accusations of media outlets being “Fake News,” yet few have thought about “Fake History,” something equally (if not more) dangerous.

“Fake news” has been around since the first hieroglyphic drawn on a Pharaoh’s tomb, the first panegyric in an imperial court, or the first stone relief carved on a Roman victory column. Rulers have almost always lied about their intentions and actions, and no more so than when at war. As Winston Churchill stated: “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.” Or, as Hiram Johnson quipped, “The first casualty, when war comes, is truth.” “You may not be interested in war, but war is interested in you.” Leon Trotsky

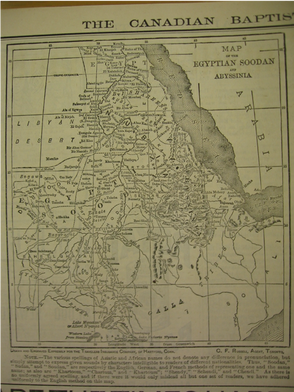

Sadly, those words of Trotsky apply today as much as in his day. Whether we identify with the just war tradition, or the pacifist tradition, or some other tradition, there is no escaping the fact that the world is a violent place and that such violence all too often intersects with our lives.[1] Today I presented my paper entitled "Canadian Protestants, the Sudan Expedition, and the New Imperialism, 1884-1885" at the annual meeting of the Canadian Society of Church History. Due to COVID-19, the meeting is online, with Zoom presentations for the next three days. Here is a link if you would like to join in the conversations and presentations.

|

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed