|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

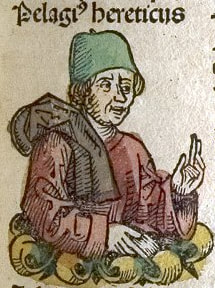

Image of Pelagius taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pelagius_from_Nuremberg_Chronicle.jpg The history of Christian theological debate is far from stellar. Accounts of violence are endemic, marring the witness of the church. For those today mired in theological disputes, there is one brief description in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History(731) that is a pithy helpful reminder of what to do (or not to do) when passions over doctrine are running high. The issue Bede describes was the spreading throughout Britain of the views of Pelagius, a theologian whose teaching had been criticized by Augustine and condemned by the Council of Ephesus (431).[1]

At stake were critical doctrines related to sin, freewill, works, and grace.[2] Bede describes a synod that was called by the church in Britain to deal with Pelagianism, a movement that he says “had corrupted the faith of Britain with its foul taint.” It should be noted that Bede’s language is not what we should copy today. In fact, his language – though typical of the time – was inflammatory and could easily lead to violence. Consider his description of the Pelagians and their teaching during the synod: “On the one side was divine faith, on the other side, human presumption; on the one side piety, on the other pride; on the one side Pelagius the founder of their faith, on the other Christ.” Elsewhere Bede portrays them as deceivers and their followers as demon possessed. All in all, setting up that type of binary is a recipe for disaster when it comes to the danger of doing harm to people, and is a style of discourse that we should avoid today. So what exactly is worth emulating in Bede’s description of the Pelagian debates? The response of the people at the synod. At the end of the debate the Pelagians were defeated, and, according to Bede, they confessed their errors. Bede then describes the response of the people in attendance. He says that the “people who were judging found it hard to refrain from violence but nevertheless signified their verdict by applause.” I find these fascinating few words in the midst of some harsh descriptions to be a helpful reminder of how to act in the midst of passionate debate. In a nutshell, choose applause over violence. Often the church’s theological discourse can be framed in a Manichean evil-versus-good binary, a recipe for violence. And choosing applause over violence seems especially hard in today’s state of political discourse. Yet, this little reminder from Bede reminds us – even when it is hard – to show restraint by choosing applause over violence. [1] Bede, Ecclesiastical History, Book 1, Chapter 17. [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pelagius. For a few books, see Benjamin B. Warfield, Augustine and the Pelagian Controversy: The Doctrines and Theology of Pelagius in the Early Christian Church (1897); Ali Bonner, The Myth of Pelagianism (OUP, 2018)

1 Comment

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed