|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

If you think today’s media is wildly biased, spewing vitriolic commentary, and destroying the fabric of the nation, you need to read up on early twentieth-century reporting during wartime Canada. It was so bad that one commentator wrote: “This prostitution of a great privilege…is the darkening curse of Canadian journalism.” The issue then was support for the nation’s war effort. It was a hostile binary world of French (Catholic) versus English (Protestant), and the tensions – stoked by the irresponsible and partisan media – turned to violence as rioters took to the streets in Quebec. With the US in the midst of an election, and Canada teetering on one, there is wisdom be gained by looking back to a time when the media had run amok and was tearing the nation apart. The issue during the First World War was conscription.[1] The political battles related to the passage of Military Service Act on 29 August 1917, and the debates surrounding the 17 December 1917 federal election and Union Government,[2] led to “all the stops to be pulled and the flood tide of Anglo-Saxon racism to be unleashed.”[3] However, conscription was the issue that threatened to divide the nation along ethnic and religious lines: in general, English Canadians were supportive of Borden’s plans to implement it, while French Canadians in Quebec were not. A riot occurred in Montreal the night the bill became law, and Borden’s electoral victory over Wilfrid Laurier and the Liberals alienated many Quebecers. More serious violence erupted in Quebec City on Easter weekend 1918: as a result over 4000 troops were stationed in Quebec City and 2000 near Montreal to ensure that the riots did not develop into a province-wide insurrection.[4]

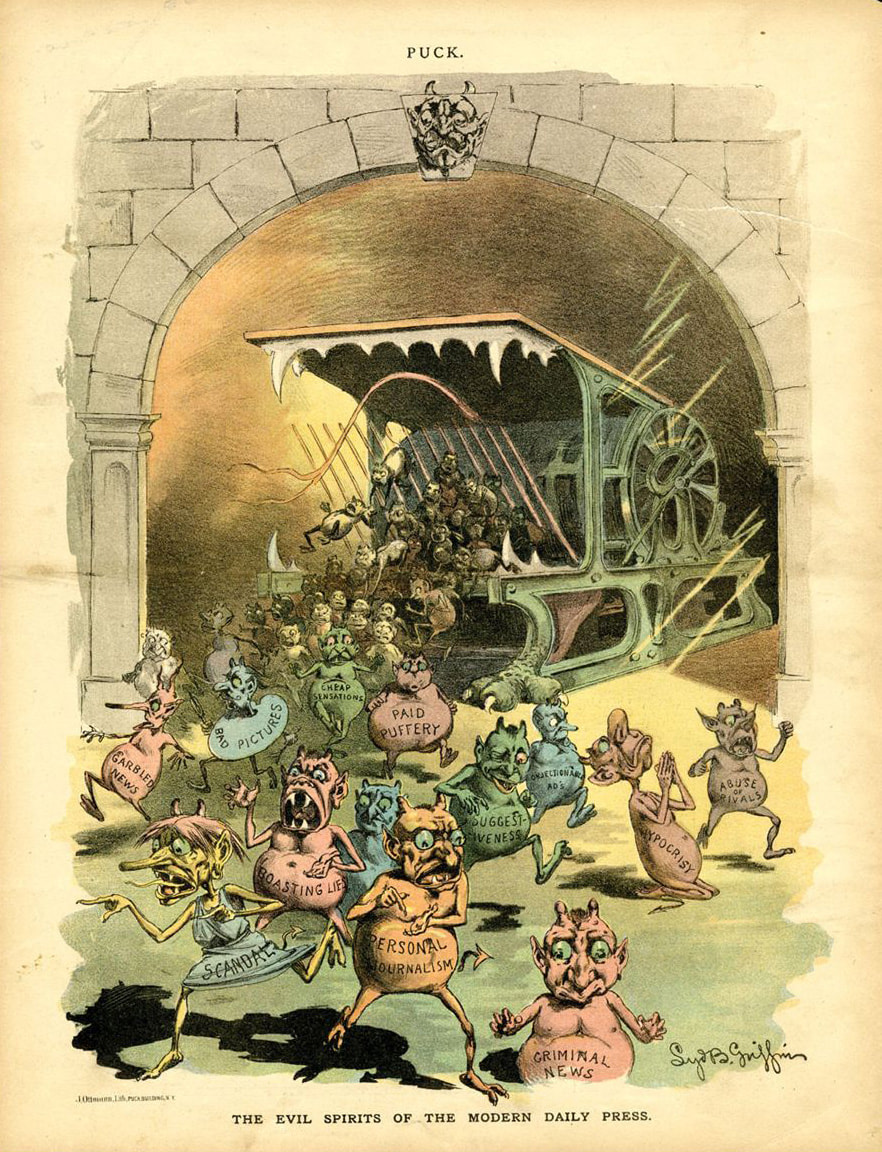

One key problem was that the media was stoking the flames of discontent, division, unrest, and violence. And that is when the Protestant religious press kicked in and tried to raise the bar and remind the secular press of its responsibility. The Westminster boldly criticized the secular papers for their abuse of privilege and opportunity: “Would it not bring about a political millennium in Canada were this whole brood of newspaper harpies and harriers themselves driven forever from the field of politics? They and their ilk have done more than all other agencies combined to befoul and embitter and poison the public life of Canada. Until the standard of ethics is as just, and the code of honor as high, in journalism as in private life or in the street or at the club, public life in Canada will continue to be a cruel and dangerous thing; and unless the lampooner and the liar are cast out of respectable newspaper circles, the curse will not be lifted, nor will the degenerate tendencies of Canadian newspaper work be arrested or turned again.”[5] The situation was considered to be so bad that certain publications had “earned the right of being disbelieved until their statements [were] independently verified.” Such a condition of “degenerate journalism” was considered to be a “menace to the country’.” The only solution, the Westminster concluded (aside from them being “driven” from the industry), was for a complete transformation of the ethics of Canadian newspaper reporting. The denominational press, in general, sought to take a higher road. To make “political capital” out of the war was to “pollute” the patriotism that was seen to be surging throughout the country.[6] The tendency to insult, slander, or otherwise treat unfairly one’s opponent was also lamented. The Westminster argued that the press was one of the “greatest blessings” and one of the “greatest curses” for “modern civilization.”[7] Sadly, it concluded, there were forces in Canada that were making the “hell of the yellow journal” a reality.

Interestingly, those two problems are the problem with reporting today.

What is fascinating is that the wartime churches led the way in calls for restraint and reforms. And while Christians cannot change the obvious bias of today’s news networks, they can listen to the prophetic critiques of the past and apply them to their own political engagement – whether as official reporters in news media or as unofficial reporters on social media. Listen to the high calling placed on Christians who engage in political commentary: “The press of Canada can be a mighty factor in keeping high ideals before the people, and in the molding of a high type of national sentiment and aspiration….[and be a force] to permeate our people with those great, eternal principles of righteousness which alone can make a nation strong?”[8] We live in an electronic age providing easy access to ready-made “news” as well as to social media that requires responsible reporting and commentary on political events. One can only hope that in the coming weeks the “Darkening Curse” of irresponsible reporting, and social media posting, may be avoided in the election frenzy. [1] Portions of this blog are taken from Gordon L. Heath, “The Protestant Denominational Press and the Conscription Crisis in Canada, 1917-1918,” Historical Studies 78 (2012): 27-46. [2] A Union Government was Borden’s attempt to unite his Conservatives with Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberals primarily in order to support conscription. Laurier and most Liberals refused the offer, but a number of Liberals (mainly those in English ridings) and Independents joined with Borden. The Union government handily won the election in 1917, but the election pitted Anglophone against Francophone in a bitter contest. [3] J.L. Granatstein and J. Mackay Hitsman, Broken Promises: A History of Conscription in Canada (Toronto: OUP, 1977), 76. [4] Martin F. Auger, “On the Brink of Civil War: The Canadian Government and the Suppression of the 1918 Quebec Easter Riots,” Canadian Historical Review, 89 4 (December 2008): 503-540. [5] “Degeneration in Canadian Journalism,” Westminster, 7 December 1901. [6] “A Disgrace to Canada,” Presbyterian Record, November 1899. This message was repeated one month later. See “A Disgrace to Canada,” Presbyterian Record, December 1899. [7] “Degeneration in Canadian Journalism,” Westminster, 7 December 1901. [8] “Our Canadian Future,” Westminster, 23 June 1900. A few months earlier the same sentiment was expressed. “the public ought to study very closely the newspaper problem, for the intelligence, the morality and the social well-being of the country, its peace at home and its prestige abroad, depends on the character and ability of its newspapers.” See “The Newspaper in Canada,” Westminster, 3 March 1900.

1 Comment

Gus Konkel

10/22/2020 05:35:27 am

My dad was a Baptist conscientious objector in the second world war. Mennonites could get alternate service, Baptists could not.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed