|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

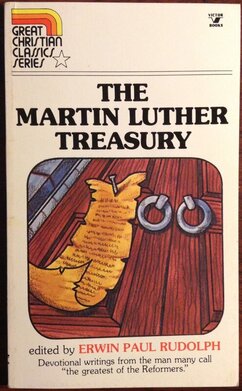

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Luther95theses.jpg

Luther was a monk-turned-professor, who became one of the most important religious reformers in western Europe in the first half of the sixteenth century. As Roland Bainton states, his writings turned the church on its head: “The man who thus called upon a saint was later to repudiate the cult of saints. He who vowed to become a monk was later to renounce monasticism. A loyal son of the Catholic Church, he was later to shatter the structure of medieval Catholicism. A devoted servant of the pope, he was later to identify the popes with Antichrist.”[1]

The pressures on Luther were immense. He had numerous debilitating physical problems, lived with a bounty on his head, experienced family tragedy, faced student expectations, and had the pressures of answering never-ending correspondence. He was also a rockstar theologian who was expected to write trailblazing theological treatises on any and every issue (and he pretty much did – his complete works comprise 52 volumes). However, in the midst of the pressures of his theological and professorial responsibilities, he managed to retain his pastoral concern for his flock. It is a joy to read how he addressed his audience as “his dear German people” – a heartfelt indication of his pastoral care for those adrift in the maelstrom of reformations. Luther cherished the common people, and he sought to nurture his followers in matters of the soul. As Owen Chadwick writes, “Luther was a man of the people and fought to bring true religion to the hearts and homes of the people; to show them that religion was not the clerical, ecclesiastical, ritual act performed in church, but the appropriation of a Gospel into life.”[2] This little abridged booklet also provides a glimpse of that concern. Consider the chapter titles:

I found this booklet to be an important reminder for me as I seek to provide theological education at a Christian seminary. I am not a rockstar church historian, but I do have pressures that demand my attention. Yet, if I want to be faithful to the life and legacy of Luther, I must remember the pastoral aspect of my calling, and the care of souls needs to be part of my faculty rhythms. And that is my most important take-away from sifting through shelves of high-octane theology books. [1] Roland Bainton, Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther (1950), 21. [2] Owen Chadwick, The Reformation (1965), 73

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed