|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

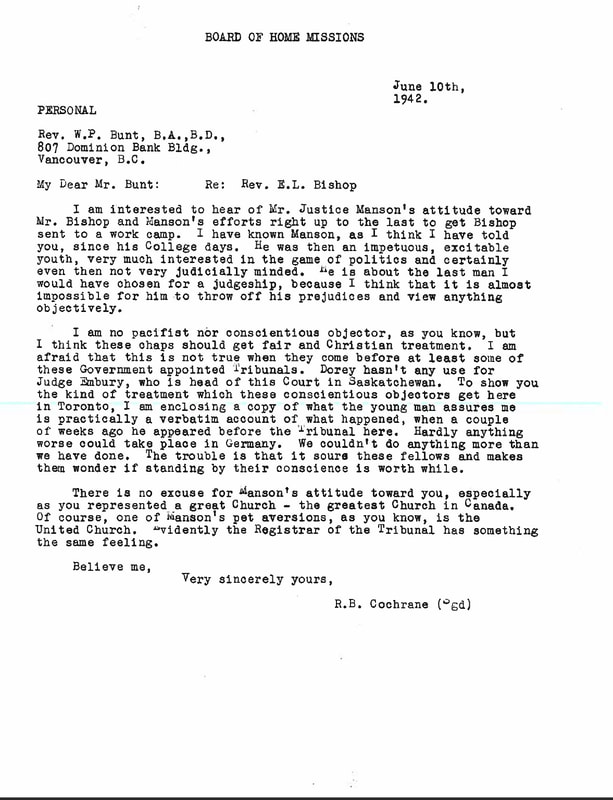

“Hardly anything worse could take place in Germany.” Not exactly the words you would expect to hear about the treatment of Canadian citizens in their own judicial system, but those feelings describe the experience of some Canadians during the last world war. A while ago I was doing research at the United Church Archives, Vancouver School of Theology, BC, and came across some letters dealing with the United Church’s attempts to assist some of its members in trouble with authorities over their conscientious objector status. We Canadians often like to think that we are exceptional, with a special respect for minority opinions. Yet, as the following account of a conscientious objector (CO) in the Second World War indicates, Canadian respect for dissent and issues related to conscience have been abandoned in a time of crisis. In fact, as the above quote from a church leader's correspondence on a trial illustrates, those upset with the perfunctory mistreatment of judges felt like they were in Nazi Germany. (Of course, wartime Canada was lightyears away from the horrendously brutal fascist regimes – the author was simply making a point with rhetorical flourish.)

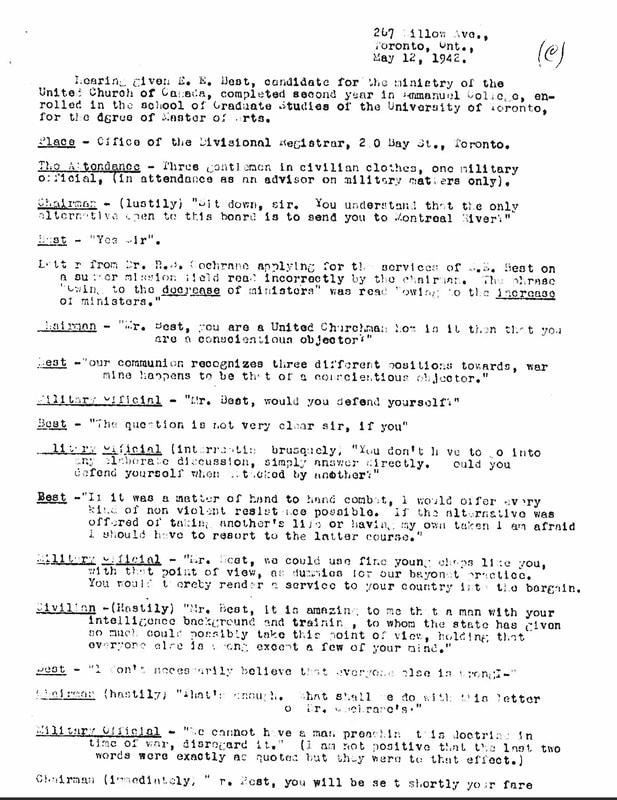

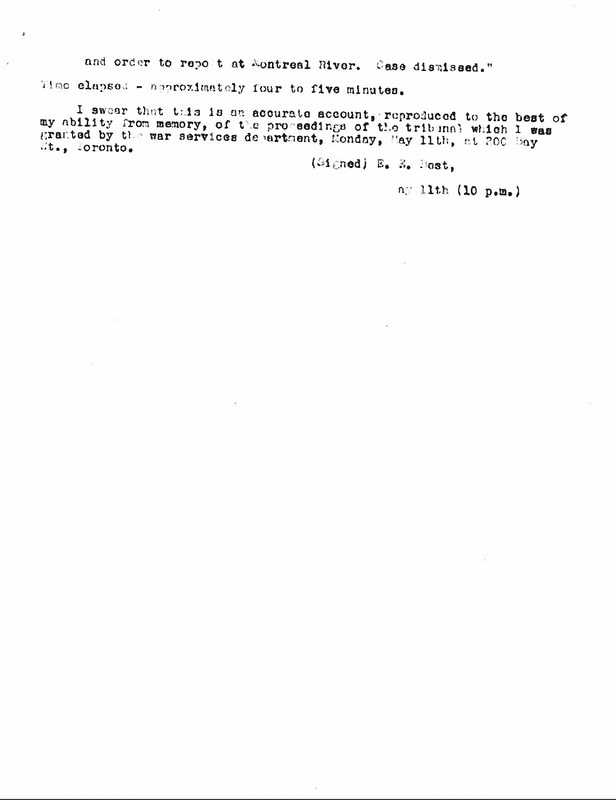

The incident in question was a verbatim account of an appearance before a judge to determine whether or not E. E. Best could be identified as a “conscientious objector” (someone whose religious beliefs did not allow him to fight as a soldier). While we are left having to judge the veracity of the account, what gives it a sense of authenticity is that what it describes was the tone and tenor of widespread Canadian contempt for wartime conscientious objectors. In fact, the judge’s suggestion that the defendant be used for “bayonet practice” reflected a lot of popular sentiment towards those who did not rally behind the nation’s war effort. Here is a transcription of the trial document.[1]. [See original documents below] 267 Willow Ave., Toronto, Ont., May 12, 1942. Hearing given E. E. Best, candidate for the ministry of the United Church of Canada, completed second year in Immanuel College, enrolled in the school of Graduate Studies of the University of Toronto, for the degree of Master of Arts. Place—Office of the Divisional Registrar, 200 Bay St., Toronto. The Attendance—Three gentlemen in civilian clothes, one military official, (in attendance as an advisor on military matters only). Chairman—(lustily) “Sit down, sir. You understand that the only alternative open to this board is to send you to Montreal River.” Best—“Yes Sir”. Letter from Dr. R.B. Cochrane applying for the services of E.E. Best on a summer mission field read incorrectly by the chairman. The phrase “Owing to the decrease of ministers” was read “Owing to the increase of ministers.” Chairman—“Mr. Best, you are a United Churchman how is it then that you are a conscientious objector?” Best—“Our communion recognizes three different positions towards war, mine happens to be that of a conscientious objector.” Military Official—“Mr. Best, would you defend yourself?” Best—“The question is not very clear sir, if you” Military Official—(interrupting brusquely,) “You don’t have to go into any elaborate discussion, simply answer directly. Would you defend yourself when attacked by another?” Best—“If it was a matter of hand to hand combat, I would offer every kind of non violent resistance possible. If the alternative was offered of taking another’s life or having my own taken I am afraid I should have to resort to the latter course.” Military Official—“Mr. Best, we could use fine young chaps like you, with that point of view, as dummies for our bayonet practice. You would thereby render a service to your country into the bargain.” Civilian—(Hastily) “Mr. Best, it is amazing to me that a man with your intelligence background and training, to whom the state has given so much could possibly take this point of view, holding that everyone else is wrong except a few of your mind.” Best—“I don’t necessarily believe that everyone else is wrong.” Chairman—(hastily) “That’s enough. What shall we do with this letter of Mr. Cochrane’s?” Military Official—“We cannot have a man preaching this doctrine in time of war, disregard it.” (I am not positive that the last two words were exactly as quoted but they were to that effect.) Chairman—(immediately,) “Mr. Best, you will be sent shortly your fare and order to report at Montreal River. Case dismissed.” Time elapsed—approximately four to five minutes. I swear that this is an accurate account, reproduced to the best of my ability from memory, of the proceedings of the tribunal which I was granted by the war services department, Monday, May 11th at 200 Bay St., Toronto. (Signed) E. E. Best May 11th (10 p.m.) The record of the wartime mistreatment of Canadian minorities and those who held minority views has been amply documented by historians[2] – but this unexpected find of one man’s mistreatment at the hands of what seems to be a biased and mean-spirited judge I found especially poignant. It is worth remembering, partly so that we have a more accurate sense of our past, but also so that we avoid similar "trials" today. [1] See Hugh Dobson Files, UCC Archives, Victoria College, Vancouver. [2] For instance, see Amy J. Shaw, Crisis of Conscience: Conscientious Objection in Canada during the First World War (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2009); Thomas P. Socknat, Witness against War: Pacifism in Canada, 1900-1945 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987); Ian McKay Manson, “The United Church and the Second World War,” The United Church of Canada: A History, edited by Don Schweitzer (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 2012). There are many more works. As for my own work, see a book chapter being published in a year or so entitled “Canadian Protestants and Conscription in the Two World Wars.”

2 Comments

Alan Hayes

12/10/2022 06:35:37 pm

Your readers may not know that there was an Alternative Service camp at the harbour where the Montreal River flows into Lake Superior. Mr. Best may never have got there, since in the following month (June 1942) most of the CO's there were sent off to the forests of British Columbia, https://uwaterloo.ca/grebel/milton-good-library/newsletters-alternative-service.

Reply

Gordon Heath

12/14/2022 07:31:38 am

Thanks Alan. The history of the camps makes for sobering reading.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed