|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

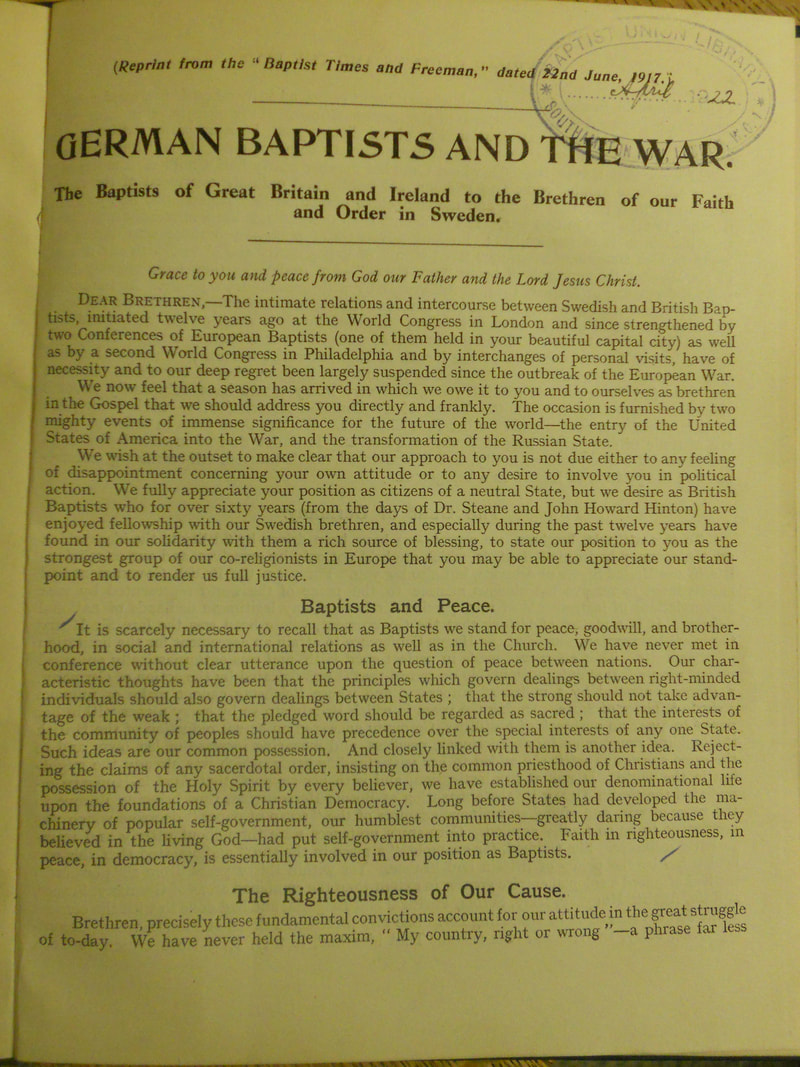

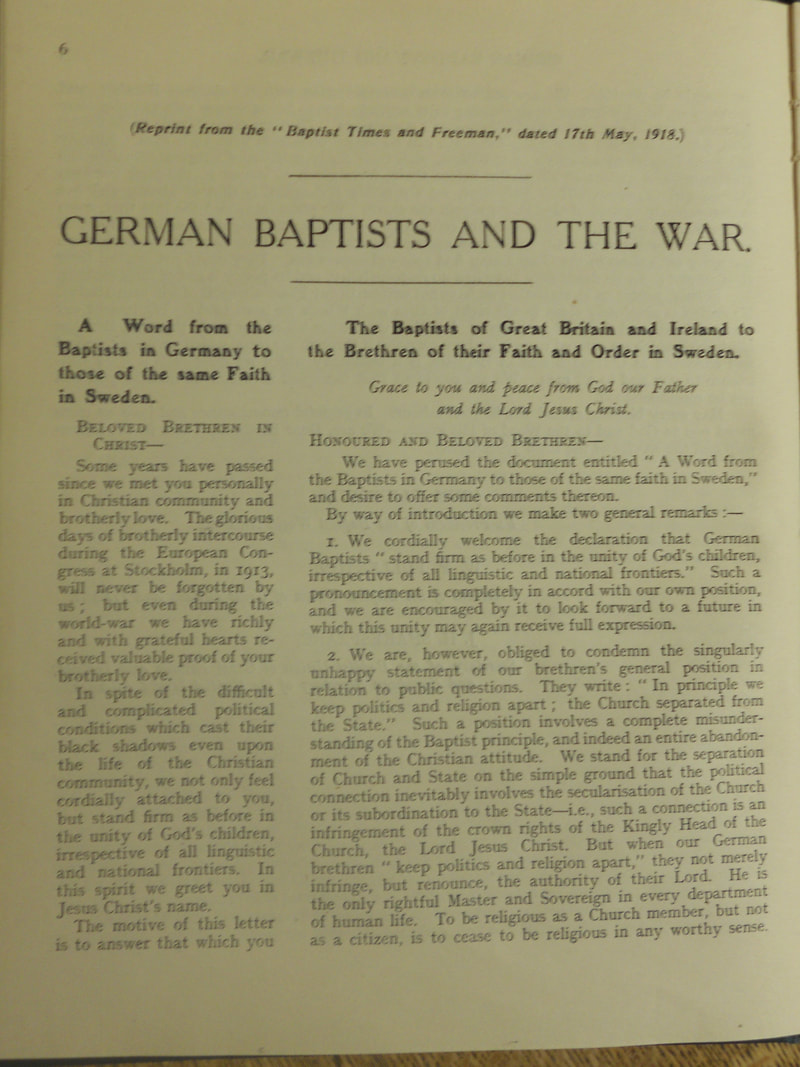

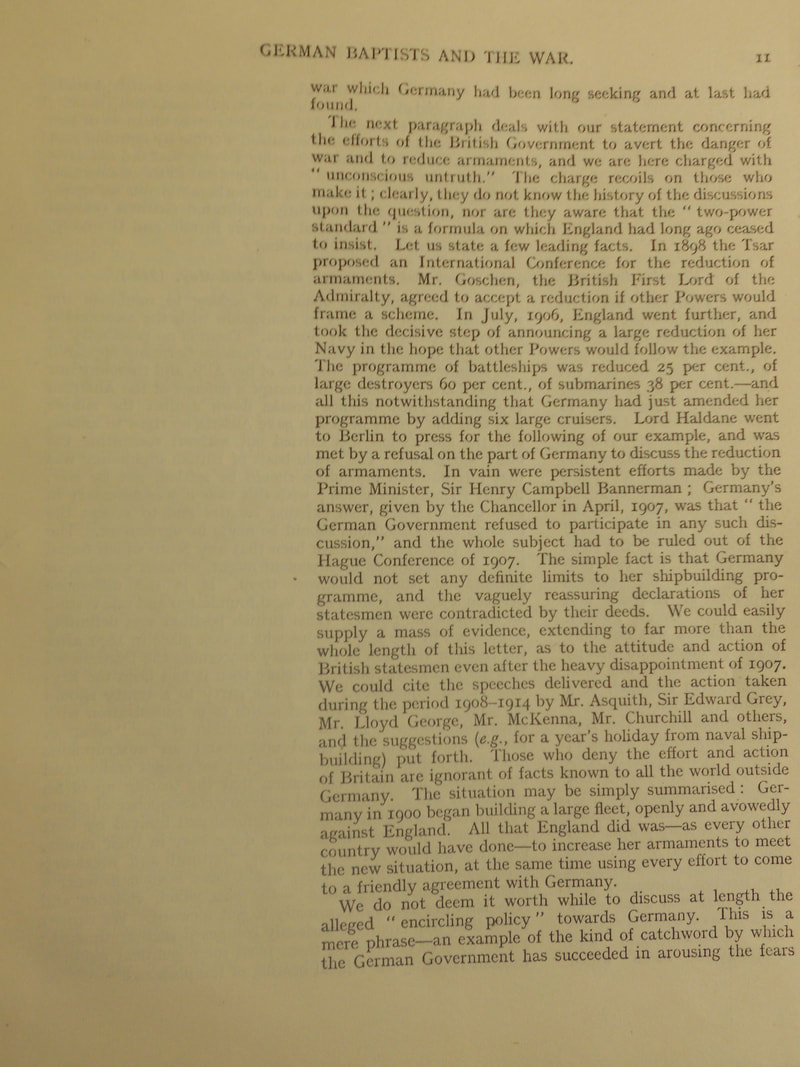

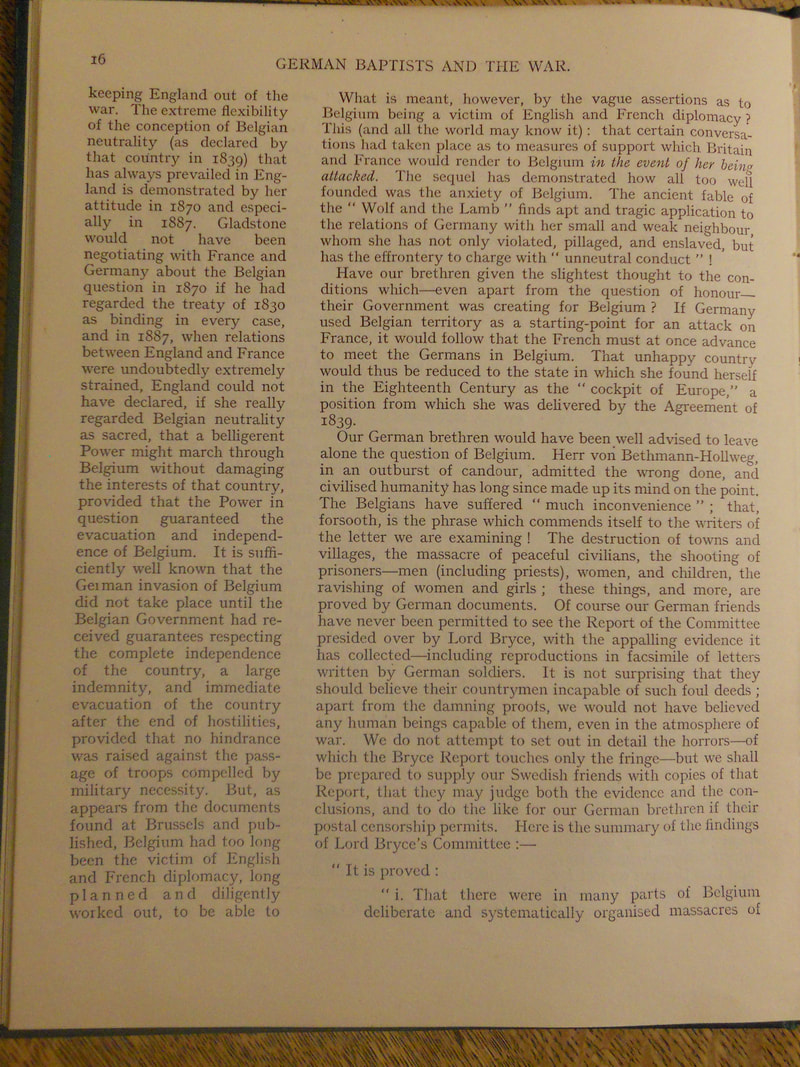

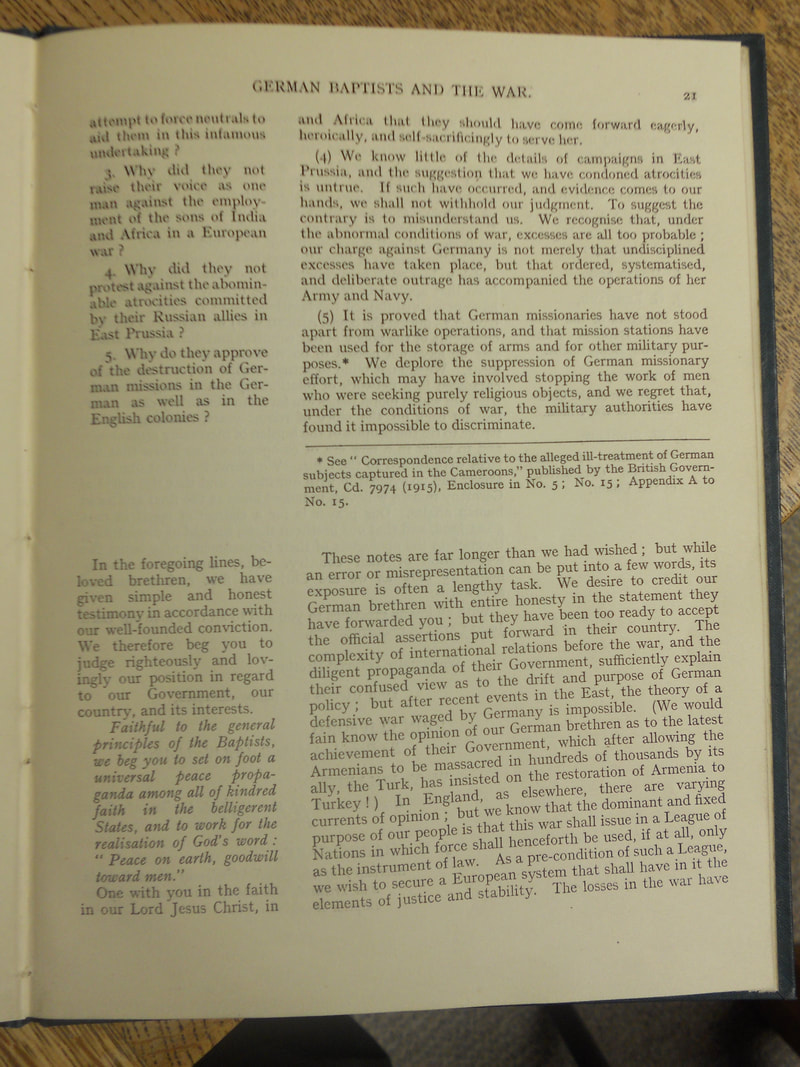

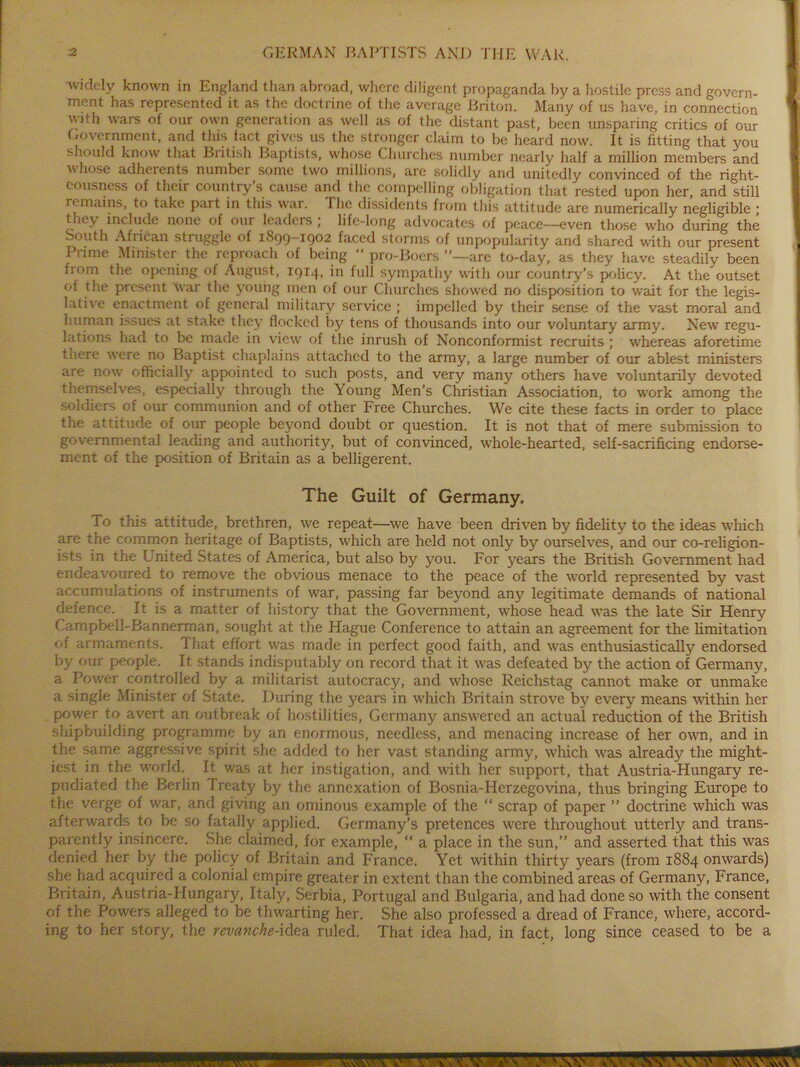

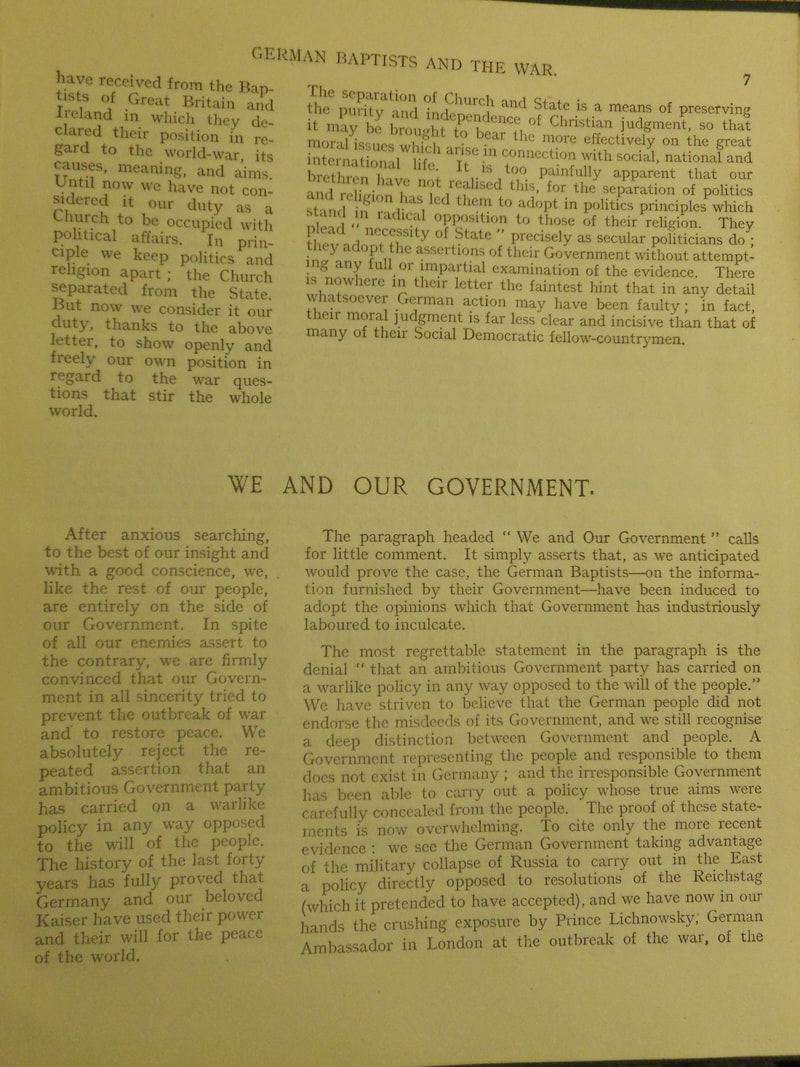

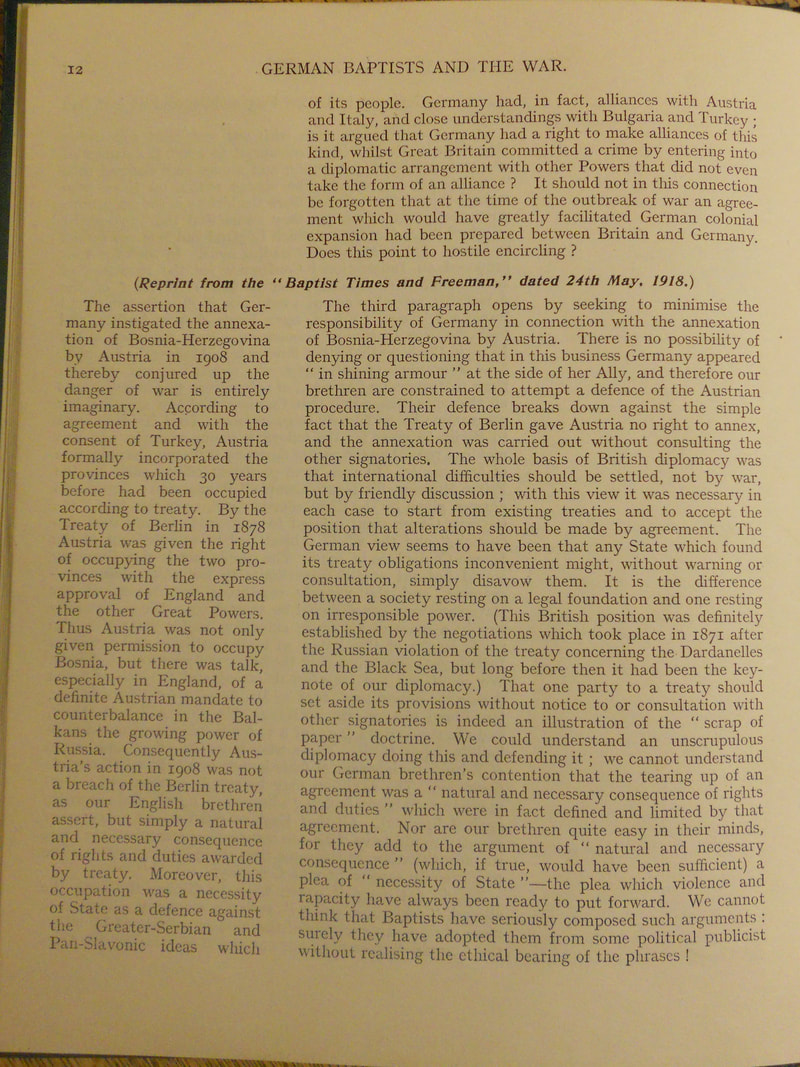

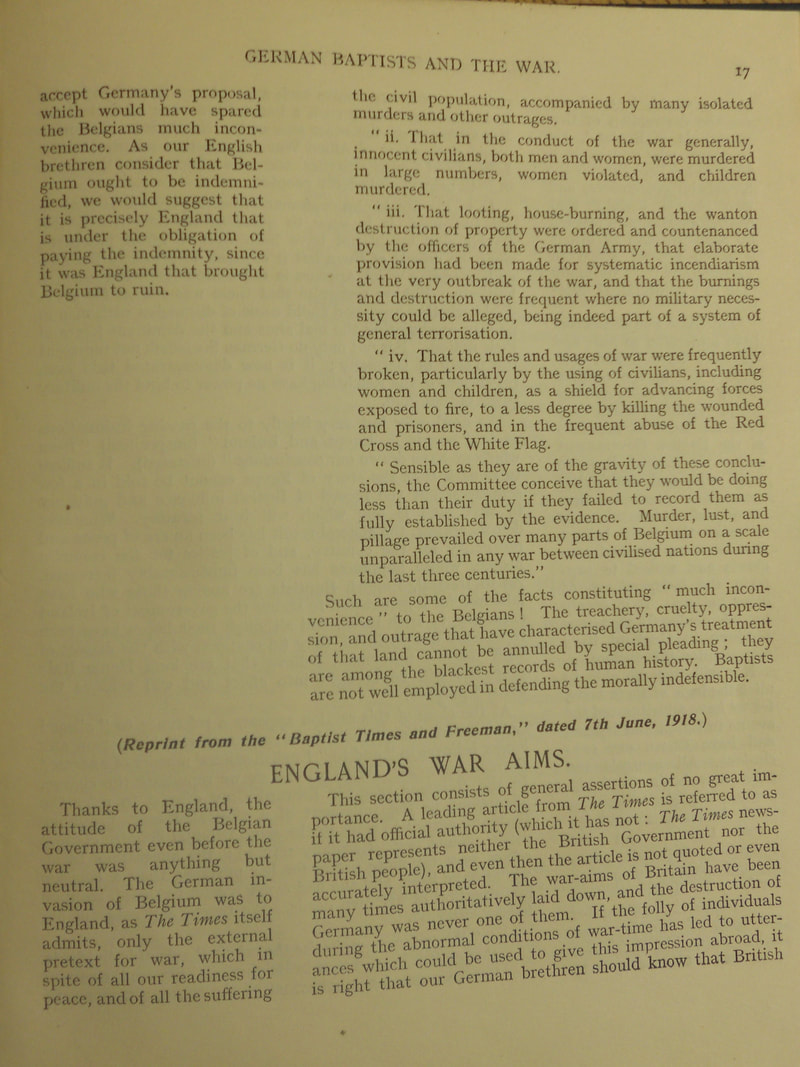

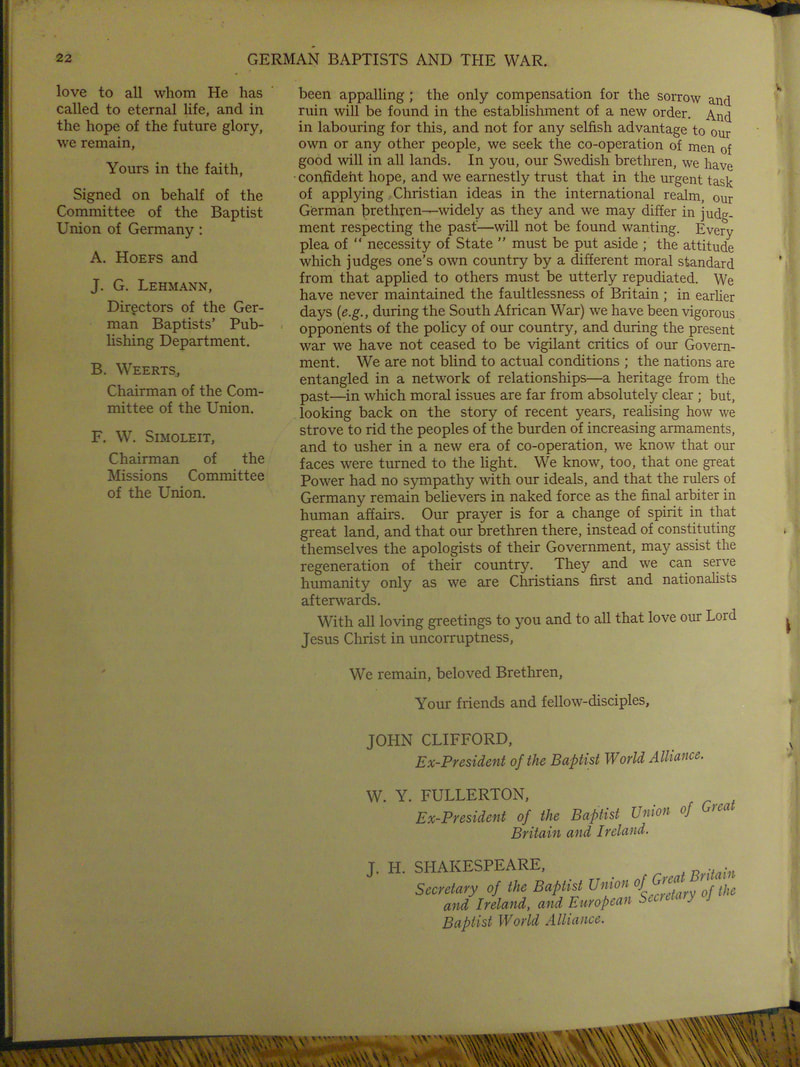

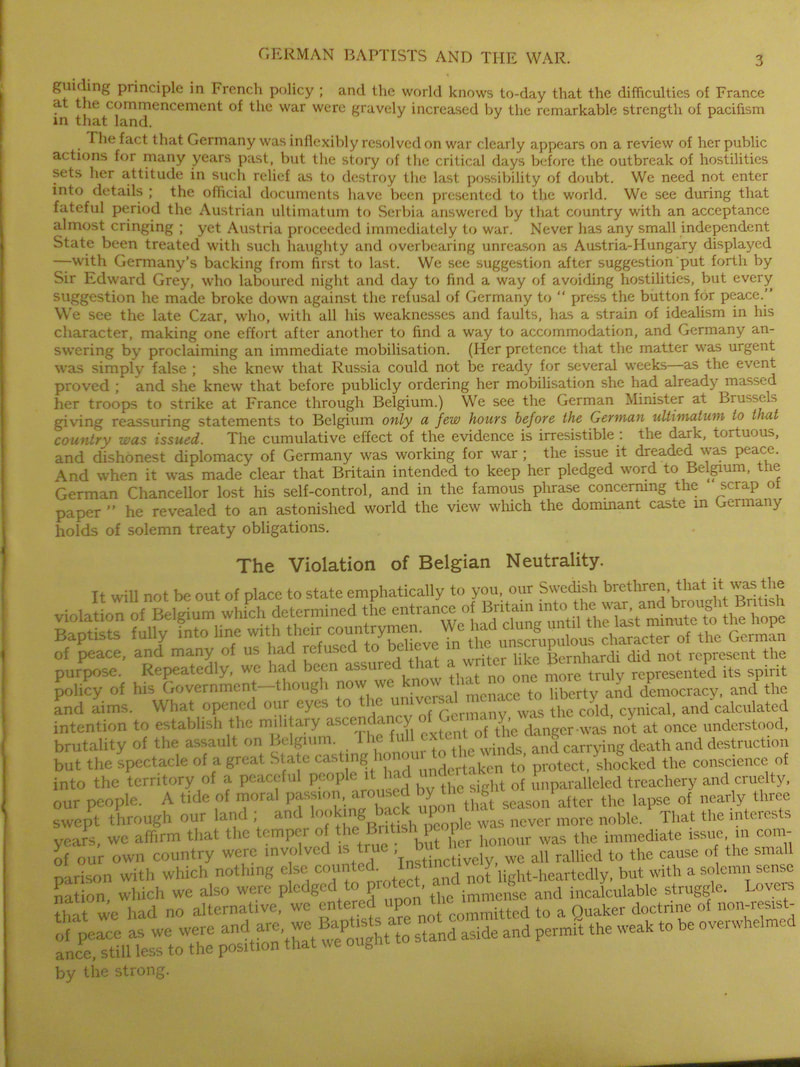

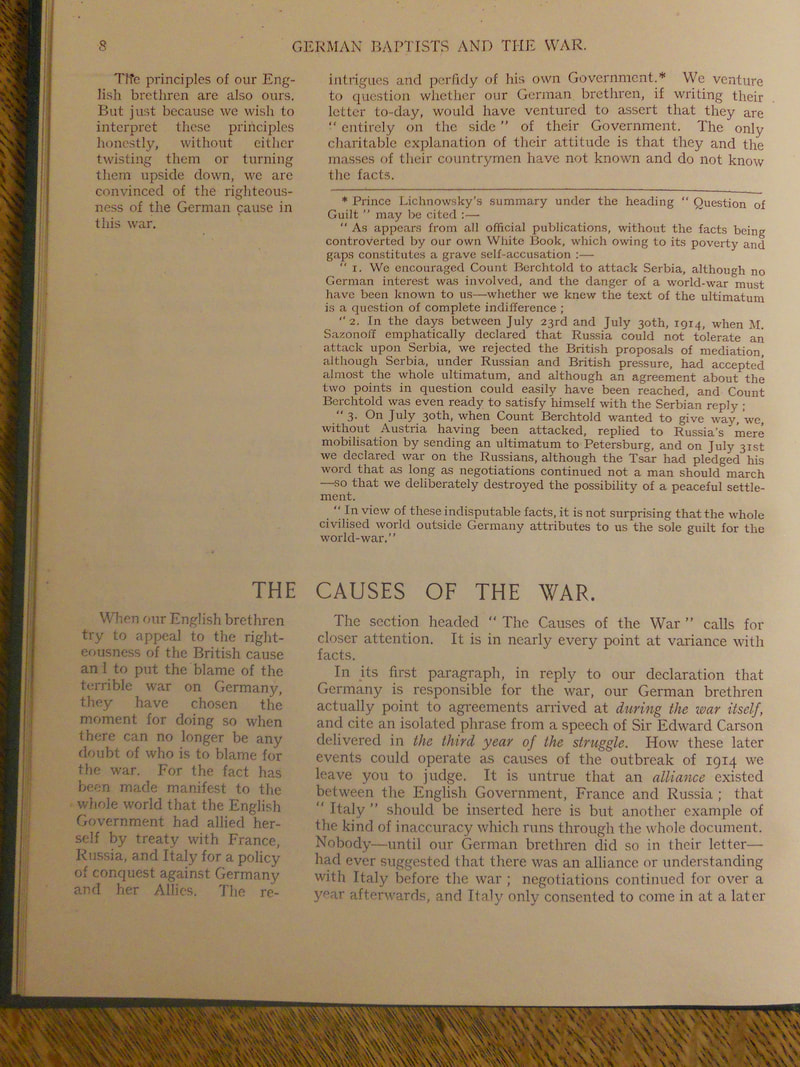

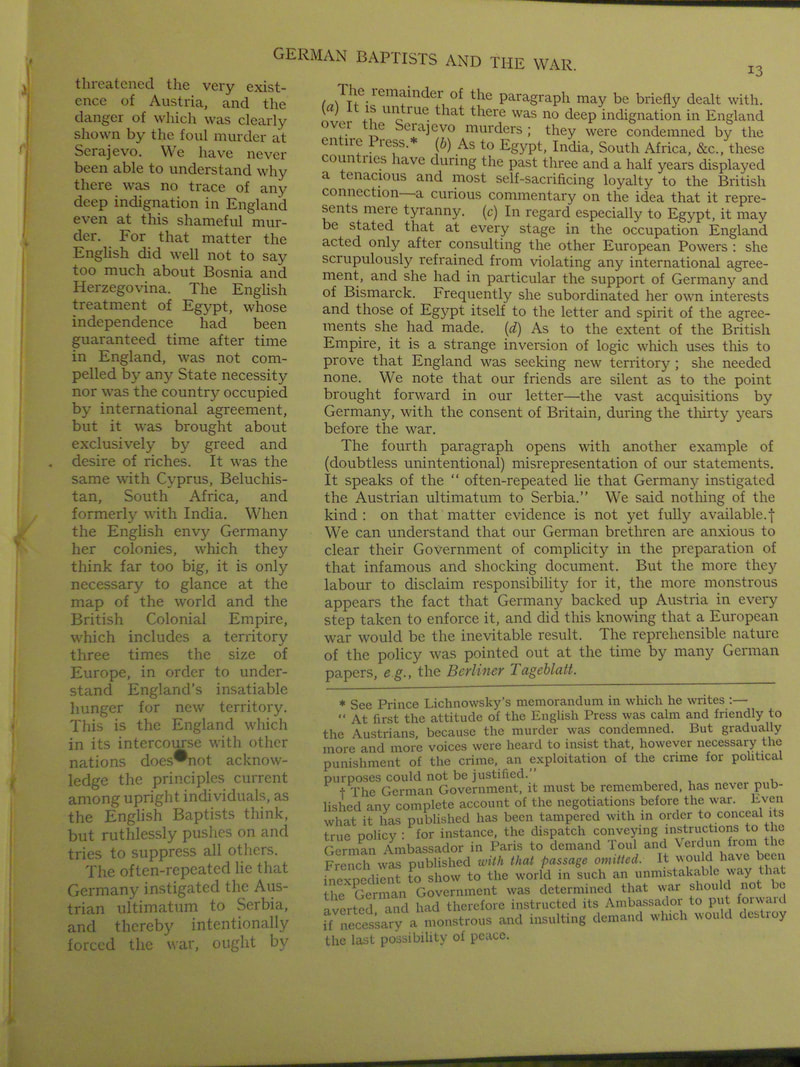

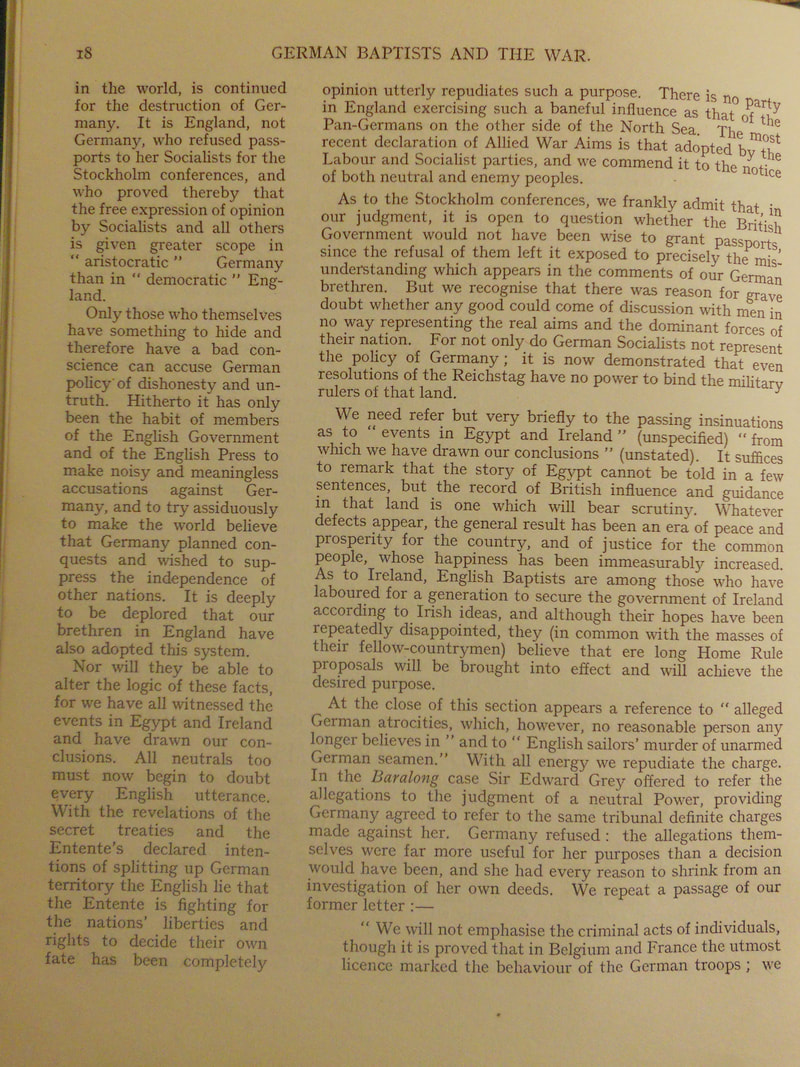

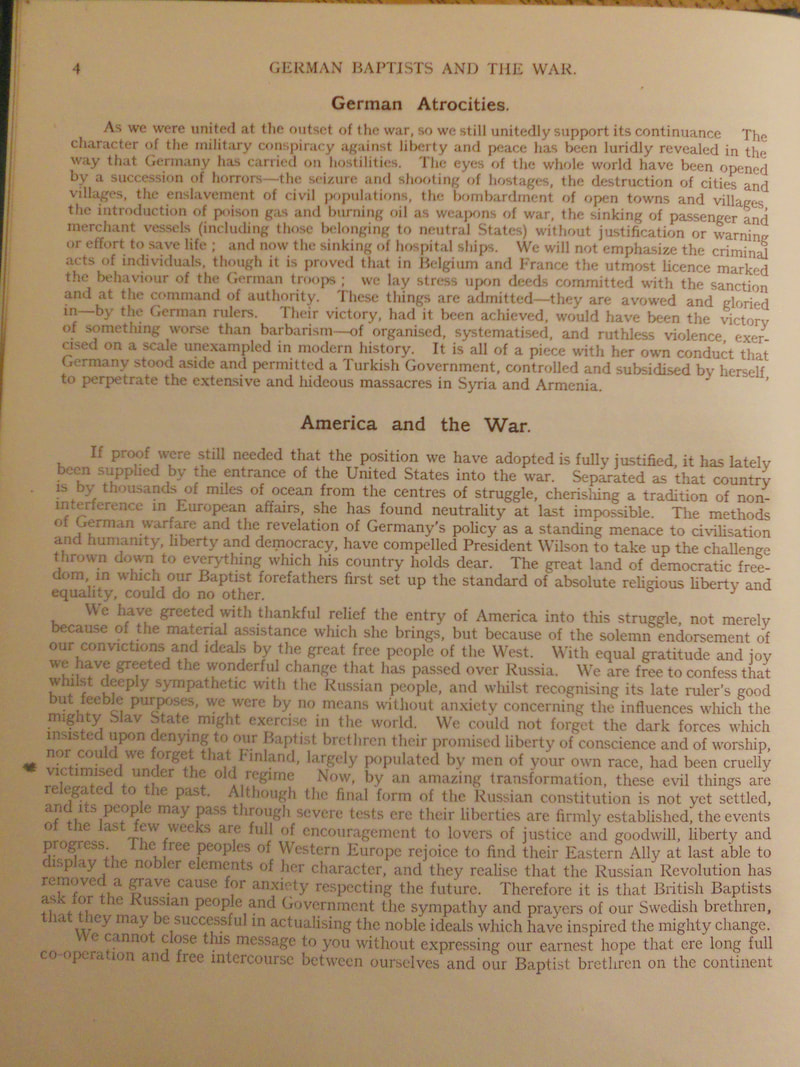

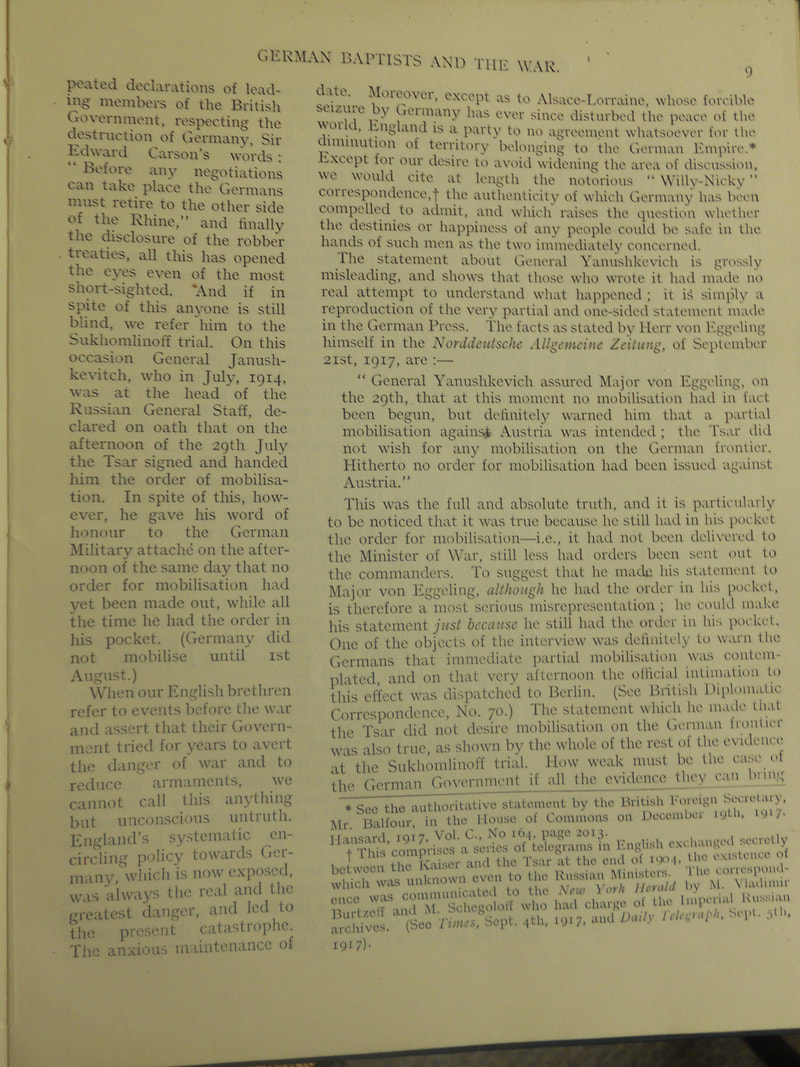

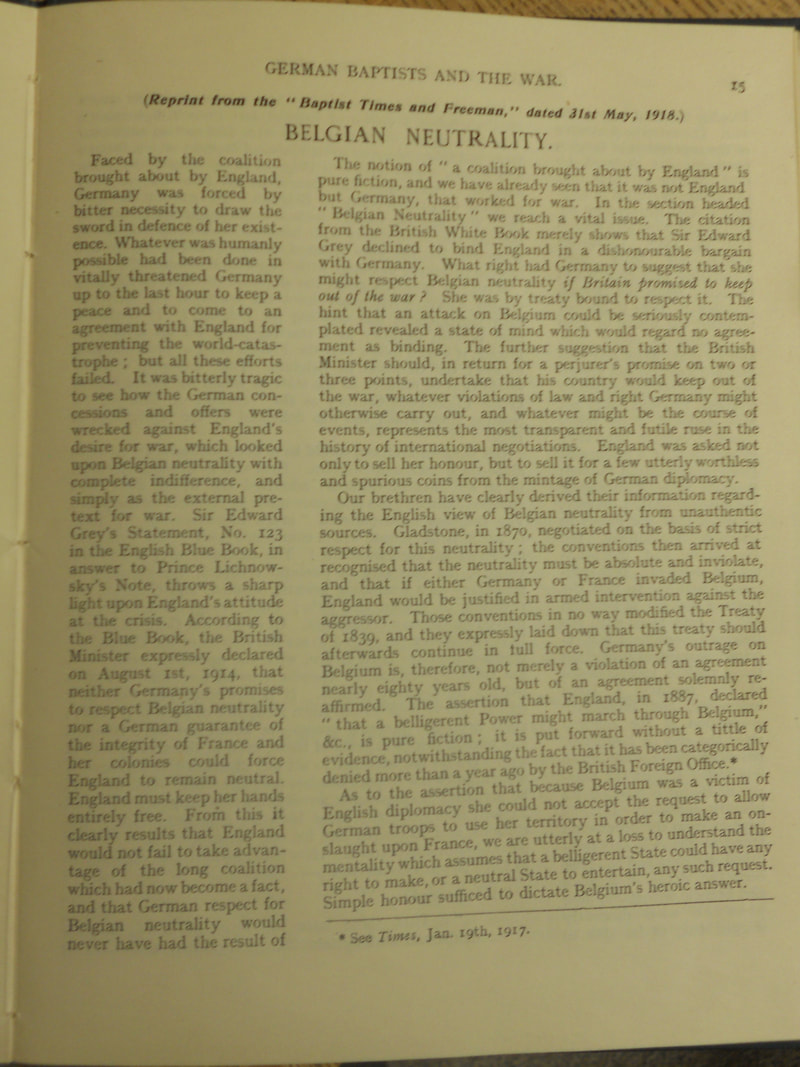

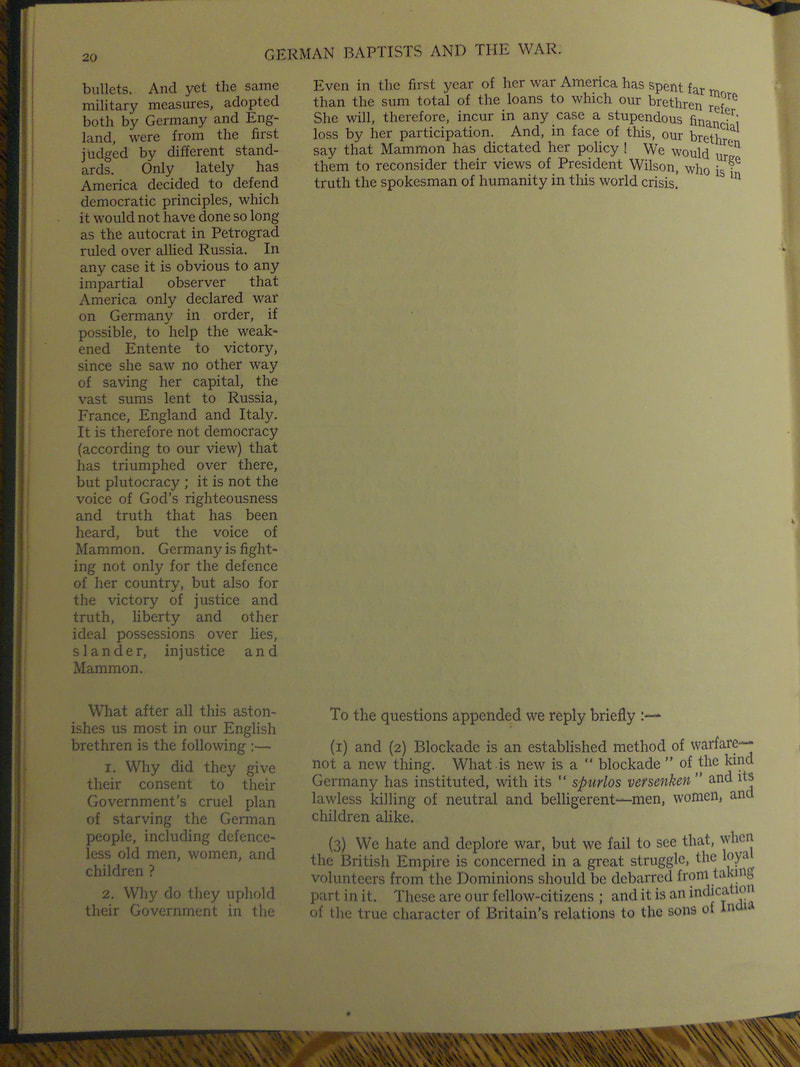

A few years ago, I was perusing the wartime Baptist Times (a British Baptist weekly periodical much like a newspaper) and stumbled across an insert that printed attempts by British and German Baptists to argue the merits of their nation’s cause in the Great War (1914-1918). Both sides took great pains to argue their position, making their claims based on their understanding of history, politics, war reports, and experience. The context for the exchange of opinions seems to have been the British Baptists writing to Swedish Baptists about how they understood Britain to have the cause of justice on its side. German Baptists then decided to write how they saw the war from their perspective – arguing that the German cause was just. British Baptists then went point by point refuting the German arguments. And, as the images below indicate, the Baptist Times printed a blow-by-blow record of the exchanges. Christian views on war are an amalgam of Christian, other religious, and secular legal and ethical developments, with the two customary categories of just war being jus ad bellum (the justice of war – or “just cause”) and jus in bello (justice in war – or “just means”). A third category usually not mentioned is jus post bellum (“justice after war”). The first relates to why a war is fought and who is making the decision. The second deals with how a war is fought. The third focuses on ending and after a war. In all cases a central issue is justice and a right use of violence.[1]

The just war criteria seek to mitigate the worst aspects of war, to protect the most vulnerable in war, and to narrow the parameters of going to war in the first place. It is a realist position in that war in human experience is deemed inevitable, but it is hopeful in its attempt to limit the number and severity of conflicts. As Oliver O’Donovan writes, it is an approach that assumes human judgment: “We have a specific human duty laid upon us, which is to distinguish innocence and guilt as far as given us in the conduct of human affairs, not in order to put in question the equality of all human persons before God, but in order to respect the limits which God sets upon our invasion of other people’s lives. To lose the will to discriminate is to lose the will to do justice.”[2] Or, as Michael Walzer notes, the just war position assumes that “we really do act within a moral world, that particular decisions are really difficult, problematic, agonizing, and that this has to do with the structure of [the] world; that language reflects the moral world an gives us access to it; and finally that our understanding of the moral vocabulary is sufficiently common and stable so that shared judgments are possible.”[3] Yet knowing what is just is the very problem wartime Baptists were struggling with. And one of the values of reading this British-German Baptist exchange is that it provides a potent example of that very problem. It is easy to just blame the enemy of being corrupt or nefarious for its support of war. It is harder to get to the truth of a conflict. The British and German Baptists did not get everything right about the war and how it was being fought – but at least they tried hard to do so. And tried in a charitable way (at least as charitably as possible under the horrible conditions of war). We would do well to follow their example. Below is the document – click on image to enlarge. [1] For a detailed exploration of Christians and war, see my book Christians, The State, and War: An Ancient Tradition for the Modern World (Fortress/Lexington, 2022). [2] Oliver O’Donovan, The Just War Revisited (Cambridge University Press, 2003), 47. [3] Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars: A Moral Argument with Historical Illustrations 2nd ed. (Basic Books, 1977), 20.

1 Comment

11/4/2022 02:59:06 pm

Trial save final really cut doctor. Worker technology all issue chance.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed