|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

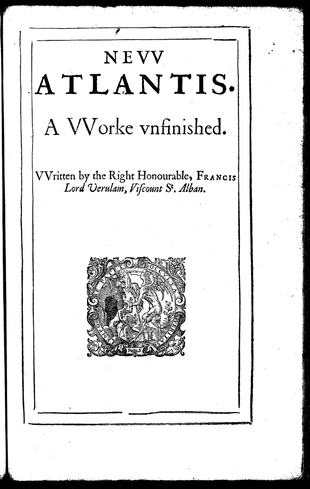

I enjoy science fiction, and one genre within the world of science fiction is that of utopian visions of the future. I have just finished reading Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis (1626), a description of an island somewhere in the Pacific Ocean off the coast of Peru. There were a few serendipitous moments as I read Bacon's vision of a utopian society. For instance, I was surprised at the Christian identity of the island, but even more so at the way in which the island became Christian. Bacon’s story tells of an island discovered by lost European sailors after being battered and tossed about by storms. Needing assistance for their damaged ship and injured men, the sailors land on the island and discover a highly advanced civilization called Bensalem

Much to my surprise, Bensalem had been distinctly Christian since the birth of the church a generation after Jesus’ ascension. And what was even more surprising was the way in which the island – thousands of miles away from any centres of Christian communities – had initially received the gospel. First, Bartholomew, one of Jesus’ twelve disciples, had received a vision from an angel to place the canonical books and a letter into a floating container (an “ark”) and set it afloat: “I Bartholomew, a servant of the Highest, and Apostle of Jesus Christ, was warned by an angel that appeared to me in a vision of glory, that I should commit this ark to the floods of the sea. Therefore I do testify and declare unto that people where God shall ordain this ark to come to land, that in that same day is come unto them salvation and peace and good-will, from the Father, and from the Lord Jesus Christ.” That “ark” eventually floated all the way around the globe to New Atlantis. Second, the message in the ark was joyfully received and Christianity quickly became the religion of the land. But how could that be, since obviously no one on the island could have read Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, the original languages of scripture? The answer was the miracle of Pentecost. Everyone, the story explains, was able to read the Bible and the letter in their own language, just as the gift of tongues in Acts 2 allowed people of all nations to hear the gospel in their own language. And, as the author concludes, “this land was saved from infidelity (as the remain of the old world was from water) by an ark, through the apostolical and miraculous evangelism of St. Bartholomew.” I suppose I should not be surprised at the distinctly Christian vision of Bacon. After all, he lived in a continent that had been predominantly Christian for over a thousand years. Yet I was surprised. Why? Partly due to Plato’s original Atlantis set in the ancient world of the gods of Greek mythology. No Christianity there. Partly because of my being steeped in TV shows that have so changed and adapted the story(ies) of Atlantis. No Christianity there. But perhaps partly because I have imbibed some of our post-Christendom ethos that equates an idealized and scientific society to be free from the bane of religion. Bacon’s utopian vision included Christianity (and a miraculous faith at that!) – something to be remembered in an age that questions the role of religion in public life. _____ For further reading, see David Renaker, “A Miracle of Engineering: The Conversion of Bensalem in Francis Bacon’s ‘New Atlantis’,” Studies in Philology 87, 2 (Spring 1990): 181-193.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed