|

My blog posts revolve around my interests and vocation as a historian: the intersection of history and contemporary church life, the intersection of history and contemporary politics, serendipitous discoveries in archives or on research trips, publications and research projects, upcoming conferences, and speaking engagements.

I sometimes blog for two other organizations, the Canadian Baptist Historical Society and the Centre for Post-Christendom Studies. The views expressed in these blogs represent the views of the authors, and not necessarily those of any organizations with which they are associated. |

|

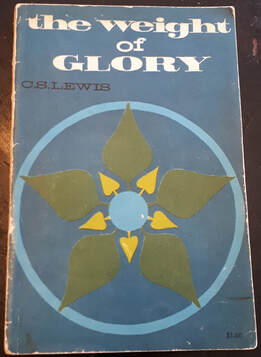

I was recently going through some of my dad’s possessions and found a small book that contained a collection of C. S. Lewis’ essays entitled The Weight of Glory (originally published in 1949). Chapter one of the book is named “The Weight of Glory” and it was an address originally delivered as a sermon in Oxford during the dark days of the Second World War. There is much to commend in the brief sermon-turned-chapter. However, the two things that immediately came to mind related to technology and secularism. First, technology. Despite what some of my family and friends may say, I am not a luddite. I see the value of technology and seek to make the best use of it in life and in education. Yet it can – at times, and in certain applications – lead to a diminishing of human contact and a concomitant decline of human worth.

Second, secularism. If there is no transcendent aspects to the human experience, and we are just or merely or only material beings, then it is hard to separate human value from the value of anything else. In fact, we are no different from any other species on the planet (except for the fact that we have been fortunate enough to ascend to the top of the food chain). In combination, technology and secularism can lead to troubling trends when it comes to the valuing of human life. And that is where Lewis’ comments enter the discussion. Rather than try to rephrase Lewis, I will provide a lengthy quote to give a sense of his profound and powerful way of describing the intrinsic value of human life and the Christian’s mission to recognize and protect it. Or as Lewis says, to carry our neighbour’s “weight of glory” on our backs. “Meanwhile the cross comes before the crown and tomorrow is a Monday morning. A cleft has opened in the pitiless walls of the world, and we are invited to follow our great Captain inside. The following Him is, of course, the essential point. That being so, it may be asked what practical use there is in the speculations which I have been indulging. I can think of at least one such use. It may be possible for each to think too much of his own potential glory hereafter; it is hardly possible for him to think too often or too deeply about that of his neighbour. The load, or weight, or burden of my neighbour’s glory should be laid daily on my back, a load so heavy that only humility can carry it, and the backs of the proud will be broken. It is a serious thing to live in a society of possible gods and goddesses, to remember that the dullest and most uninteresting person you talk to may one day be a creature which, if you saw it now, you would be strongly tempted to worship, or else a horror and a corruption such as you now meet, if at all, only in a nightmare. All day long we are, in some degree, helping each other to one or other of these destinations. It is in the light of these overwhelming possibilities, it is with the awe and the circumspection proper to them, that we should conduct all our dealings with one another, all friendships, all loves, all play, all politics. There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilization—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendours. This does not mean that we are able to be perpetually solemn. We must play. But our merriment must be of that kind (and it is, in fact, the merriest kind) which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken each other seriously—no flippancy, no superiority, no presumption. And our charity must be a real and costly love, with deep feeling for the sins in spite of which we love the sinner—no mere tolerance or indulgence which parodies love as flippancy parodies merriment. Next to the Blessed Sacrament itself, your neighbour is the holiest object presented to your senses. If he is your Christian neighbour he is holy in almost the same way, for in him also Christ vere latitat—the glorifier and the glorified, Glory Himself, is truly hidden.”[1] [1] C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (Eerdmans, 1965), 14-15.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

May 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed